Dyslipidemia; from Physiology to Treatment

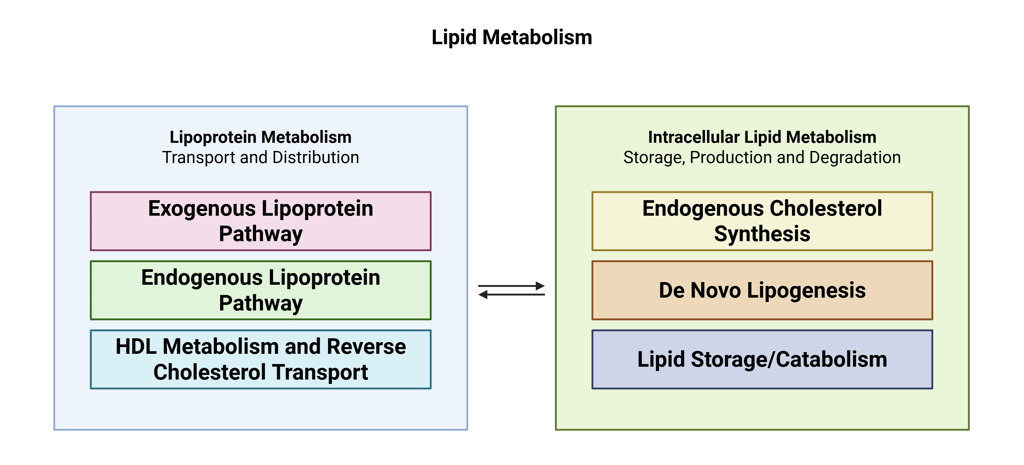

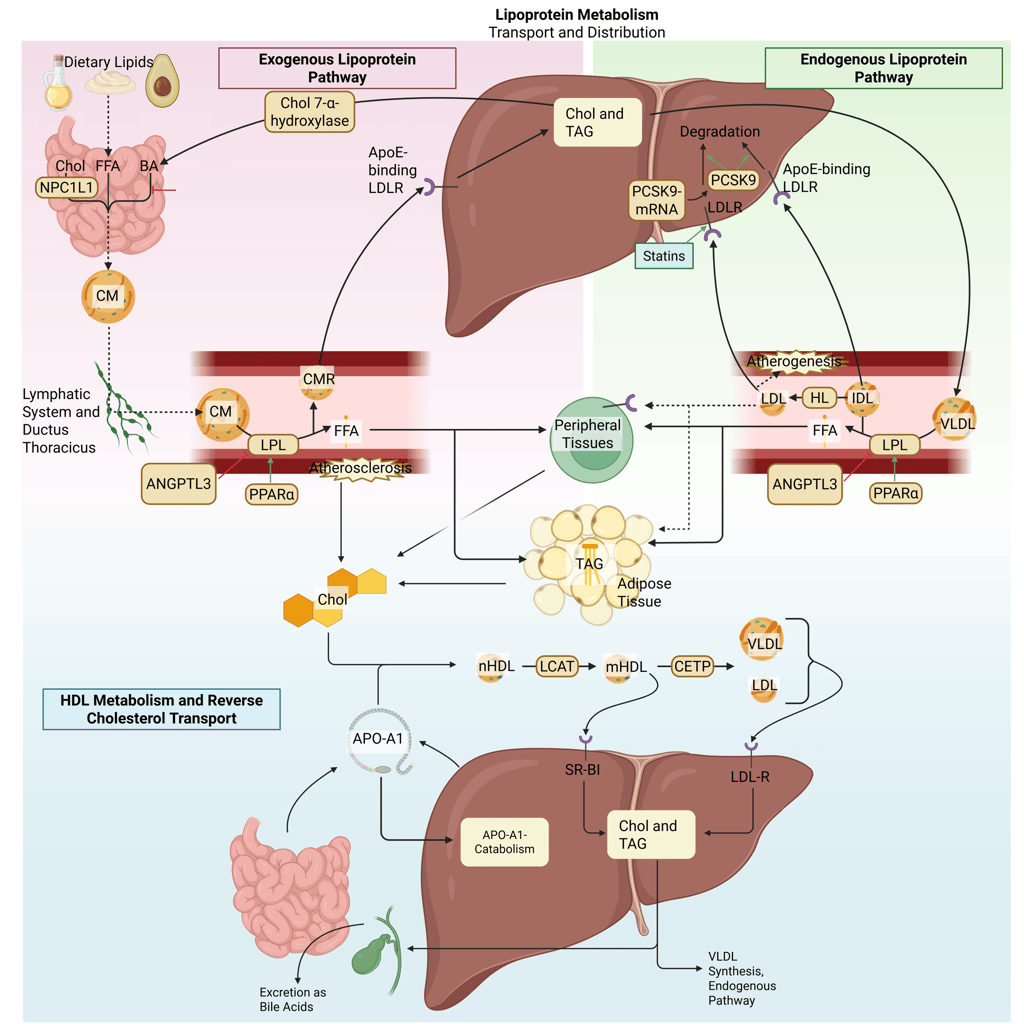

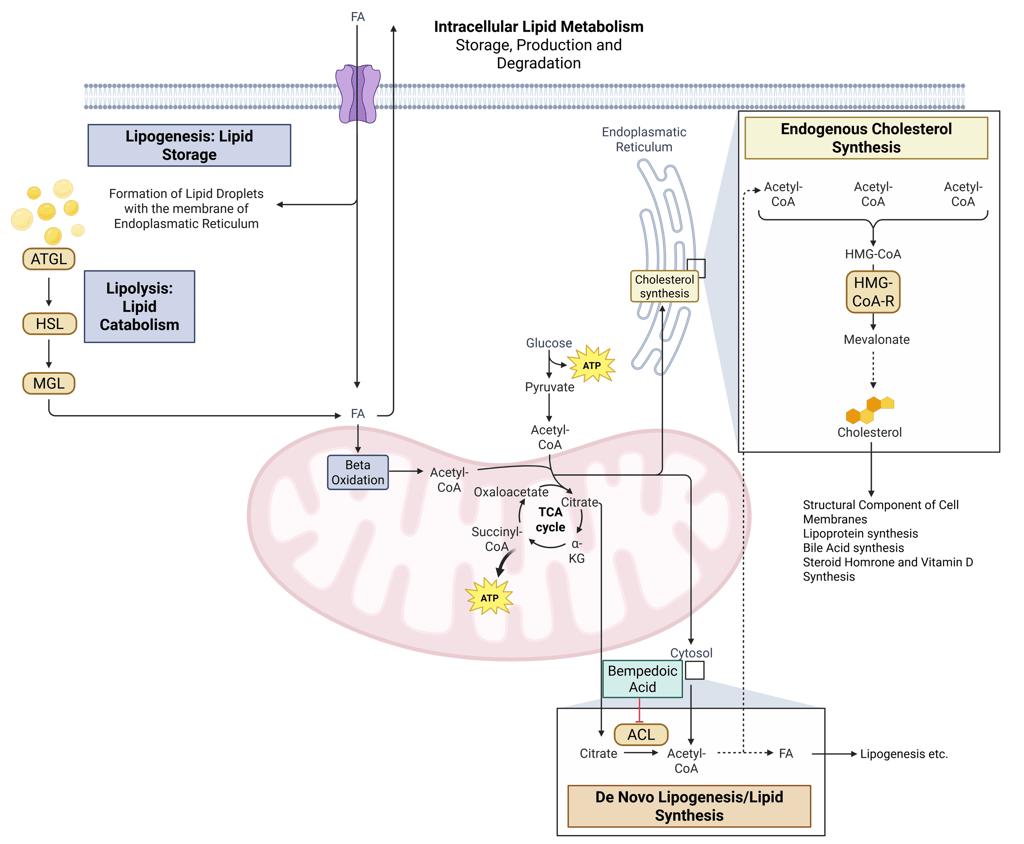

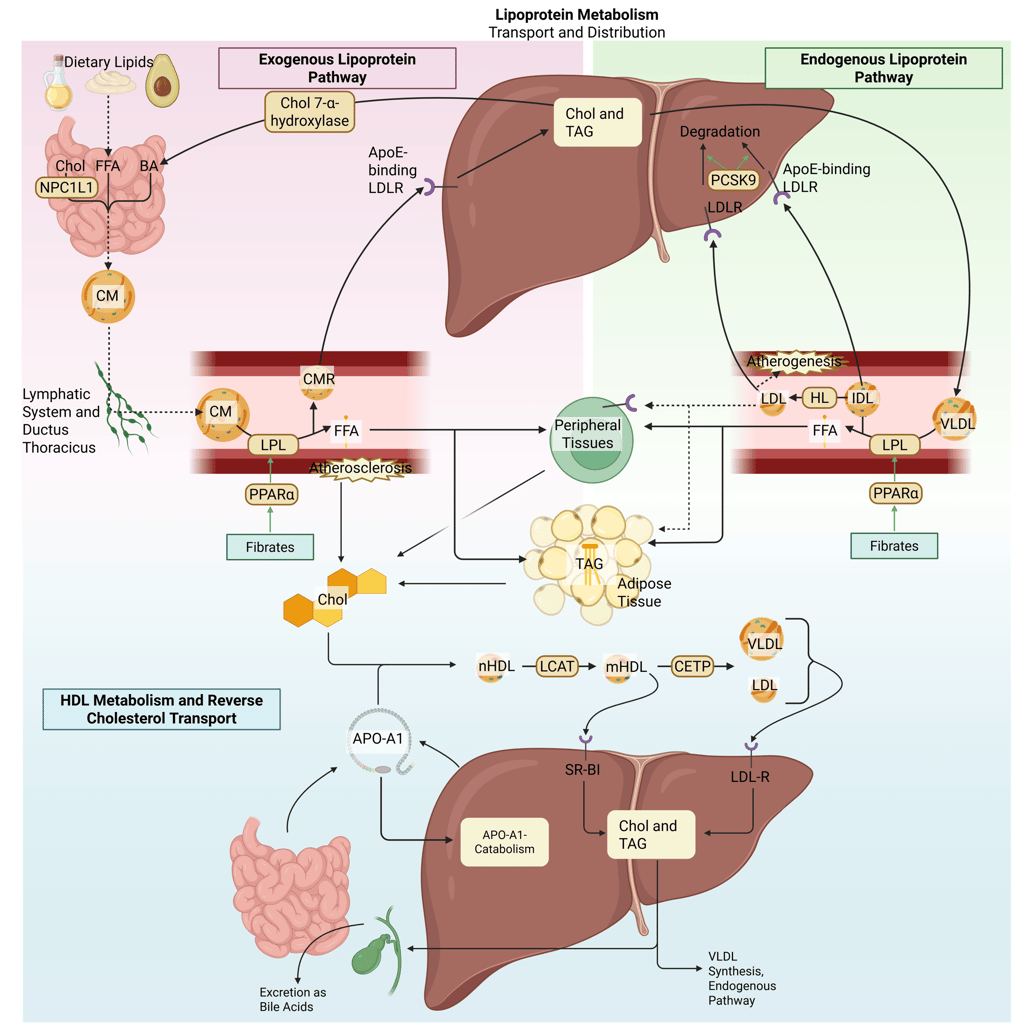

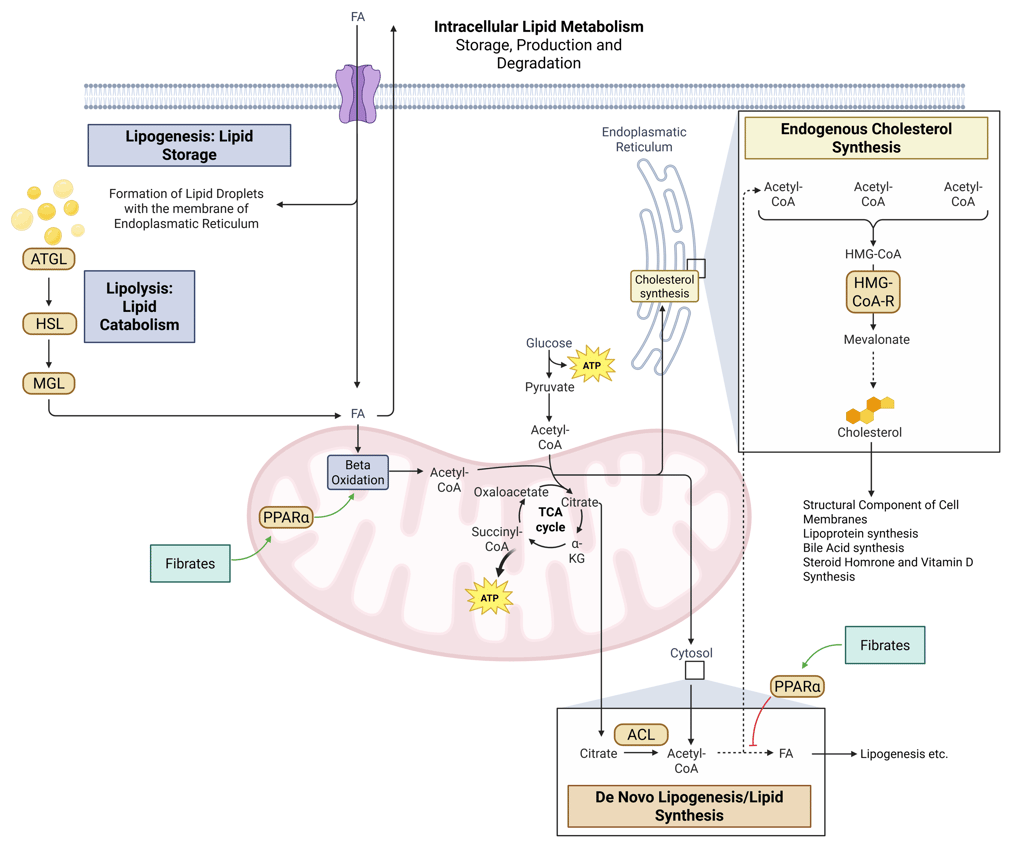

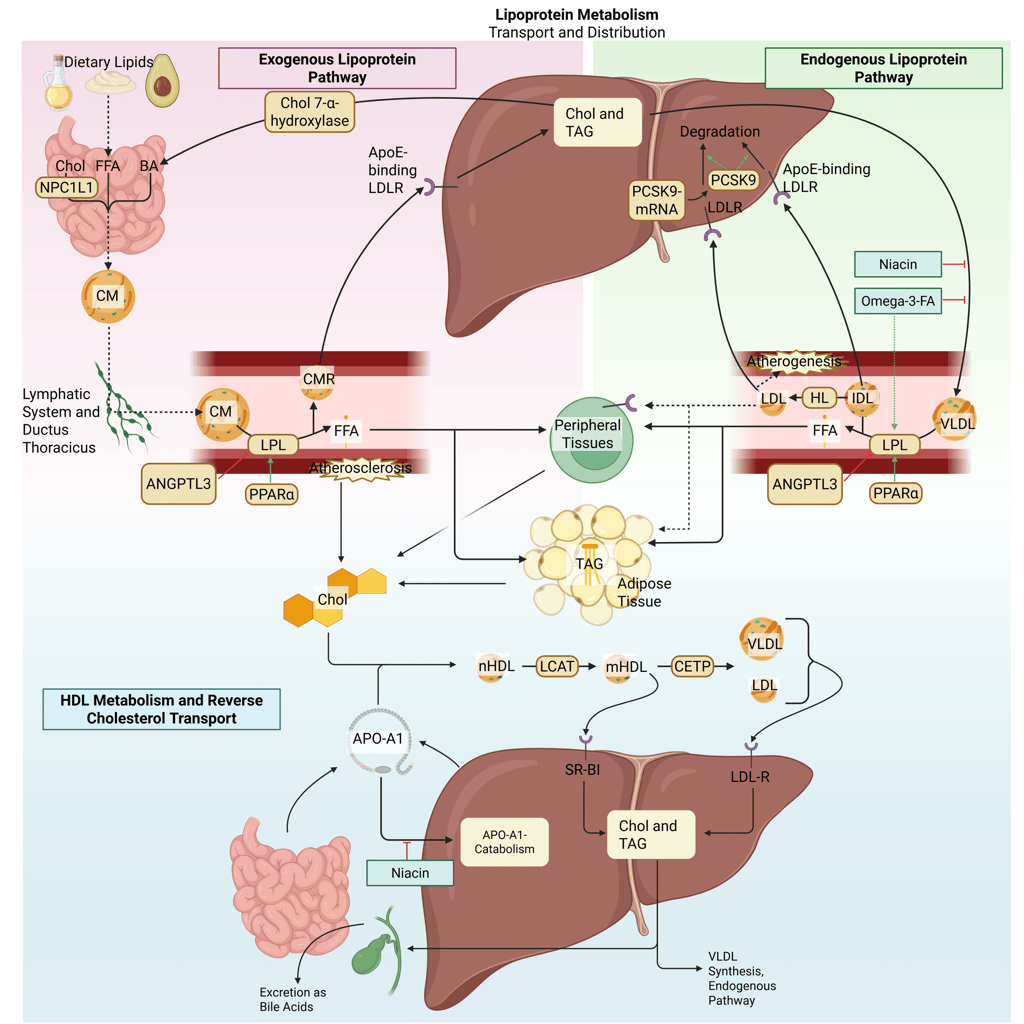

Lipid metabolism can be understood as comprising two tightly interdependent components.

The first is lipoprotein metabolism, which governs the transport, exchange, and clearance of lipids between the liver, intestine, and peripheral tissues.

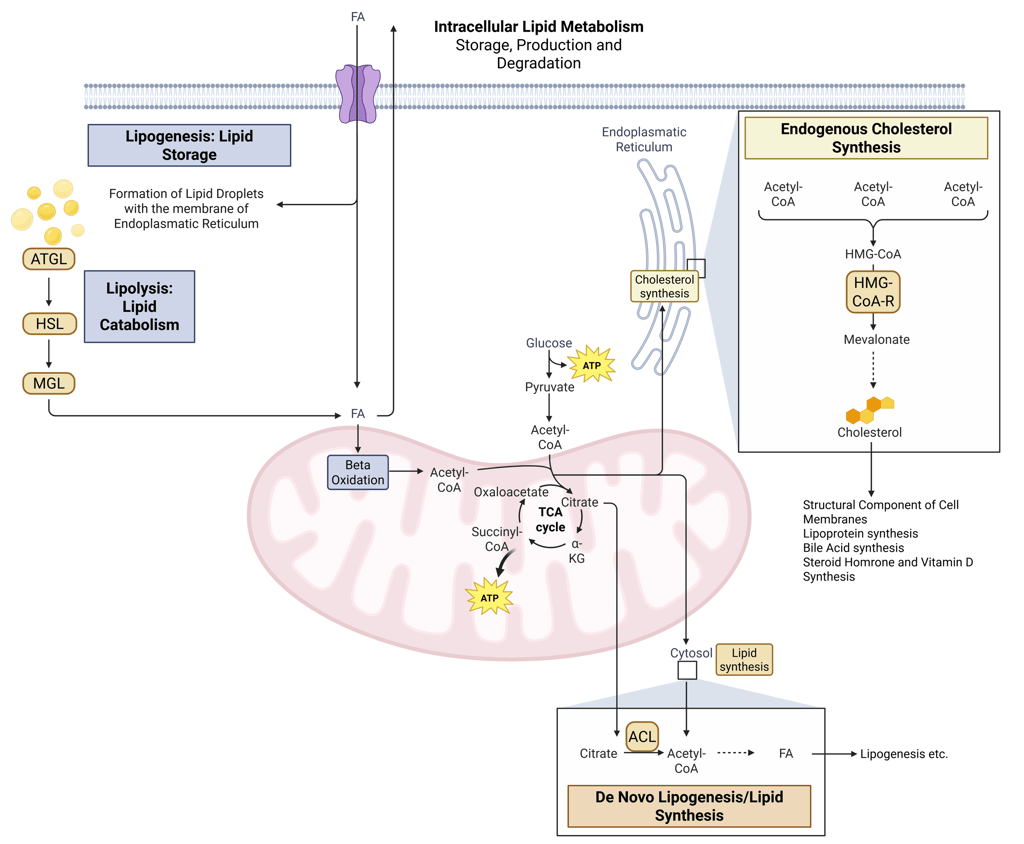

The second is intracellular lipid metabolism, which involves the synthesis, storage, and breakdown of lipids to generate energy locally or supply substrates to other tissues.

These two systems are deeply interconnected: intracellular pathways generate lipid species that are packaged into lipoproteins and released into the circulation, while circulating lipoproteins deliver lipid cargoes that directly shape cellular lipid handling. A firm grasp of these processes is essential for understanding how specific pharmacological treatments modulate the lipid profile.

If you haven’t done so already, I recommend reading the clinical pearl on the core concepts of lipid metabolism first. It provides the physiological foundation needed to interpret the therapeutic mechanisms shown in the illustrations below.

Exercise

There are many pharmacological strategies available to treat dyslipidemia. Before examining their individual mechanisms, try to (1) predict where each agent acts within lipid metabolism (see illustration below) and (2) which component of the lipid profile it primarily affects.

Pharmacological agents:

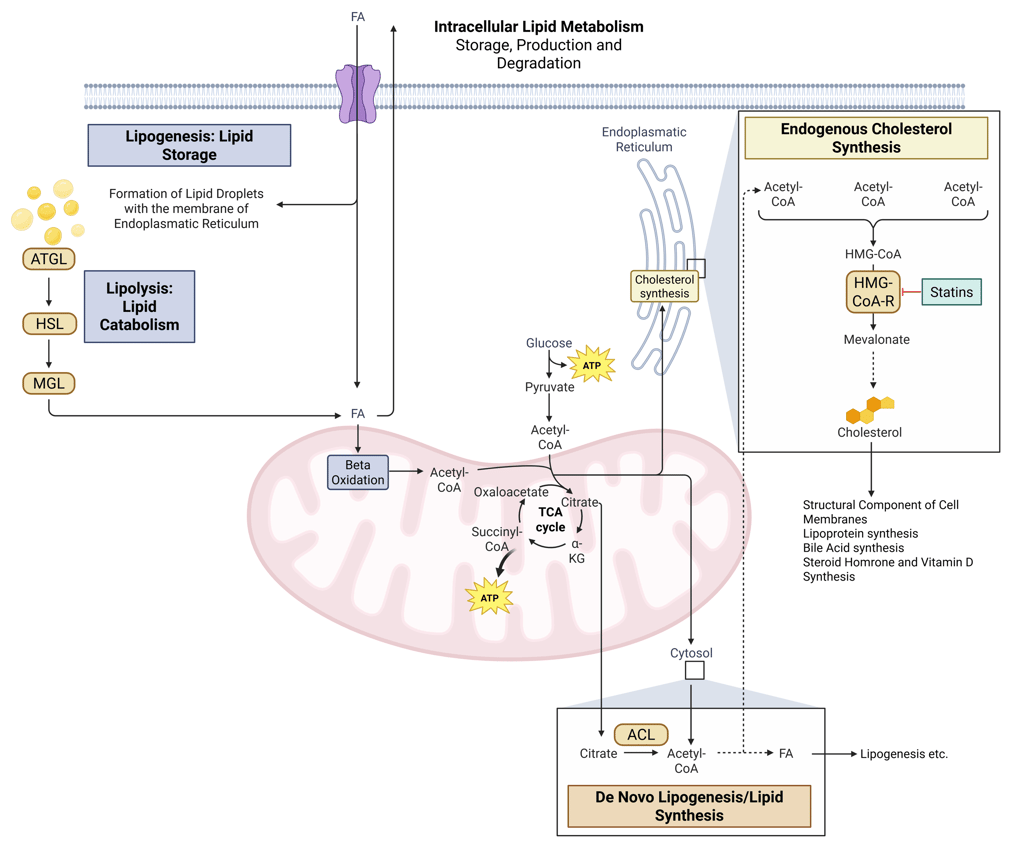

Statins

Bempedoic acid

PCSK9 inhibitors

Inclisiran

Niacin

Fibrates

Bile acid sequestrants

ANGPTL3 inhibitors

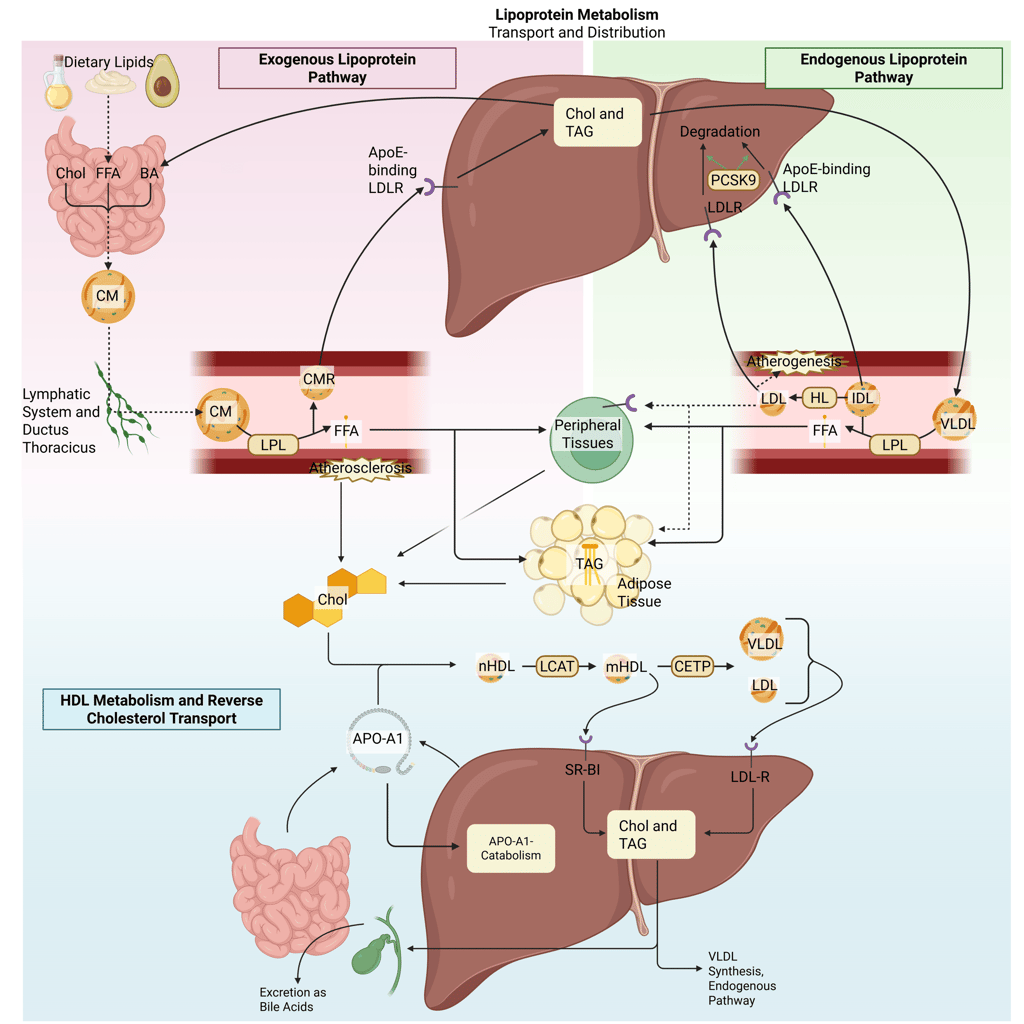

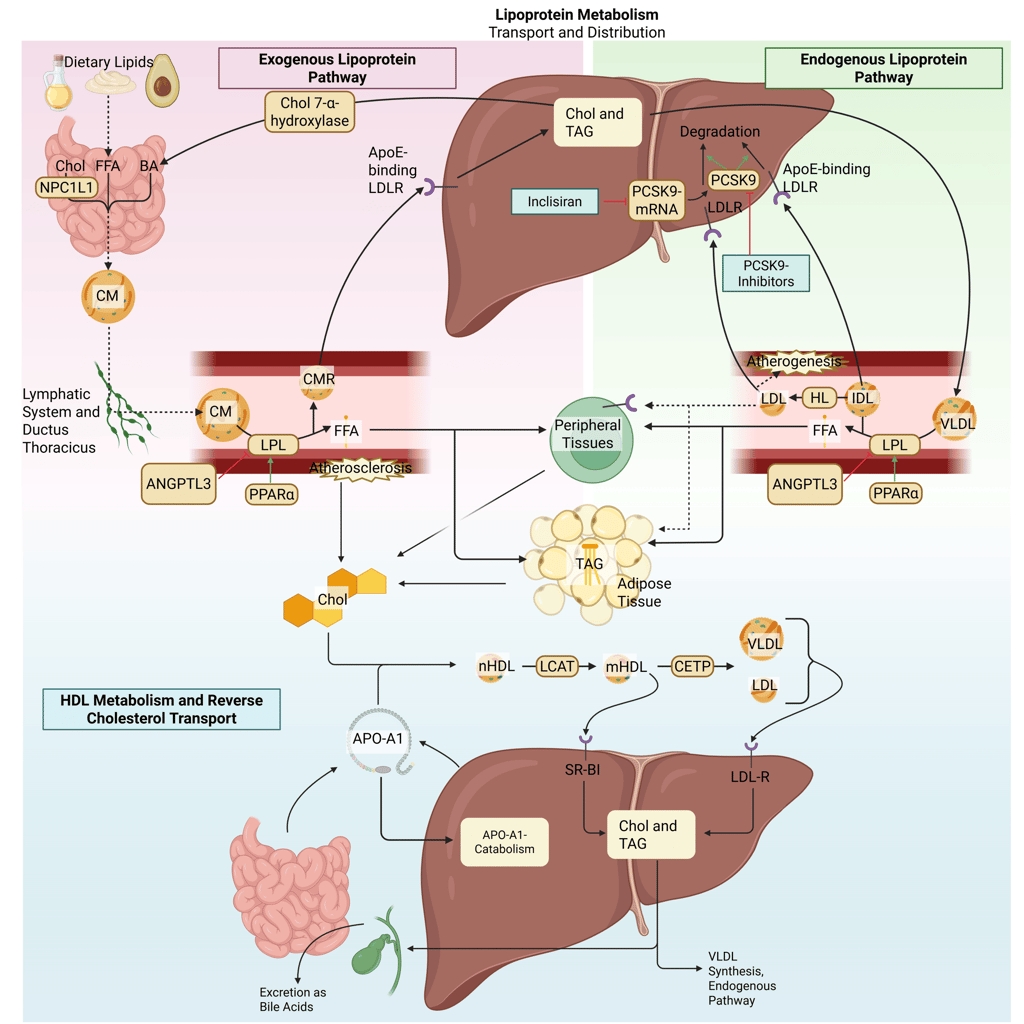

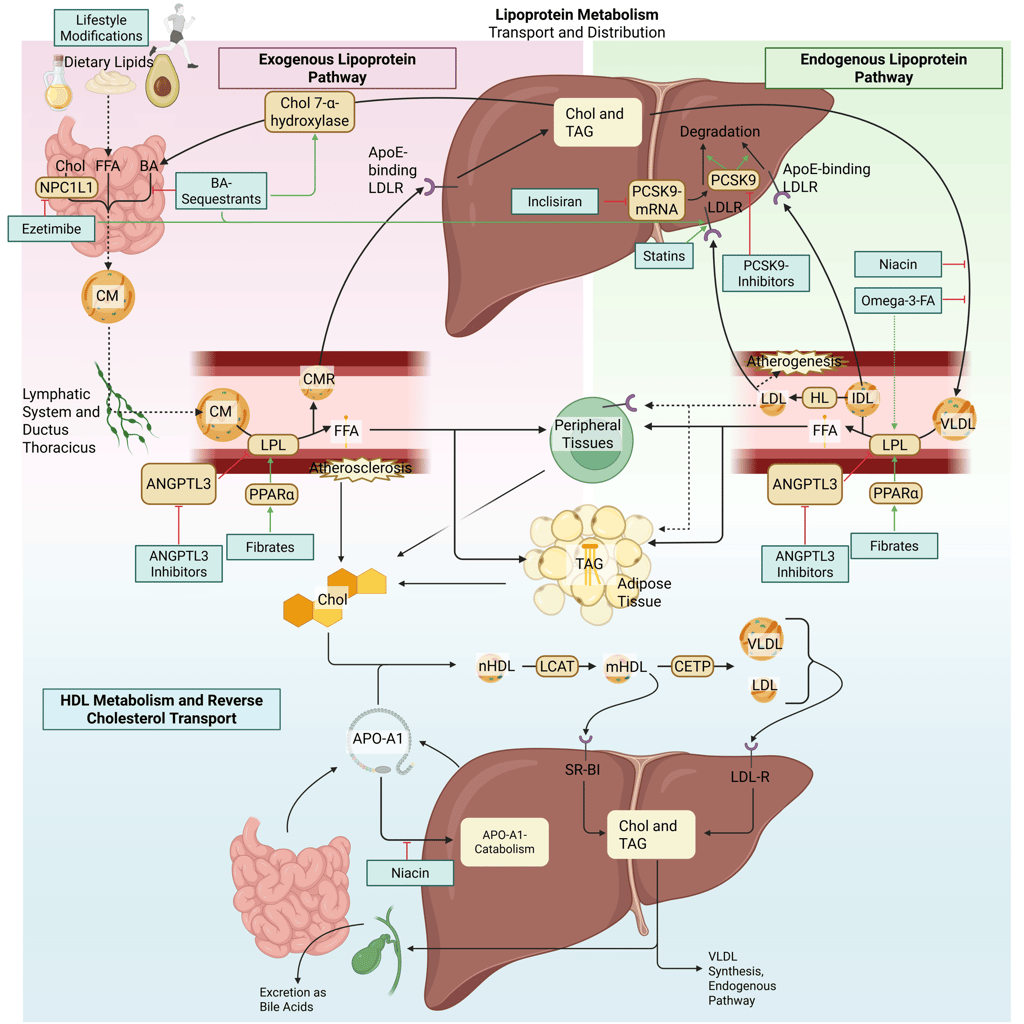

Detailed Illustration of the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor

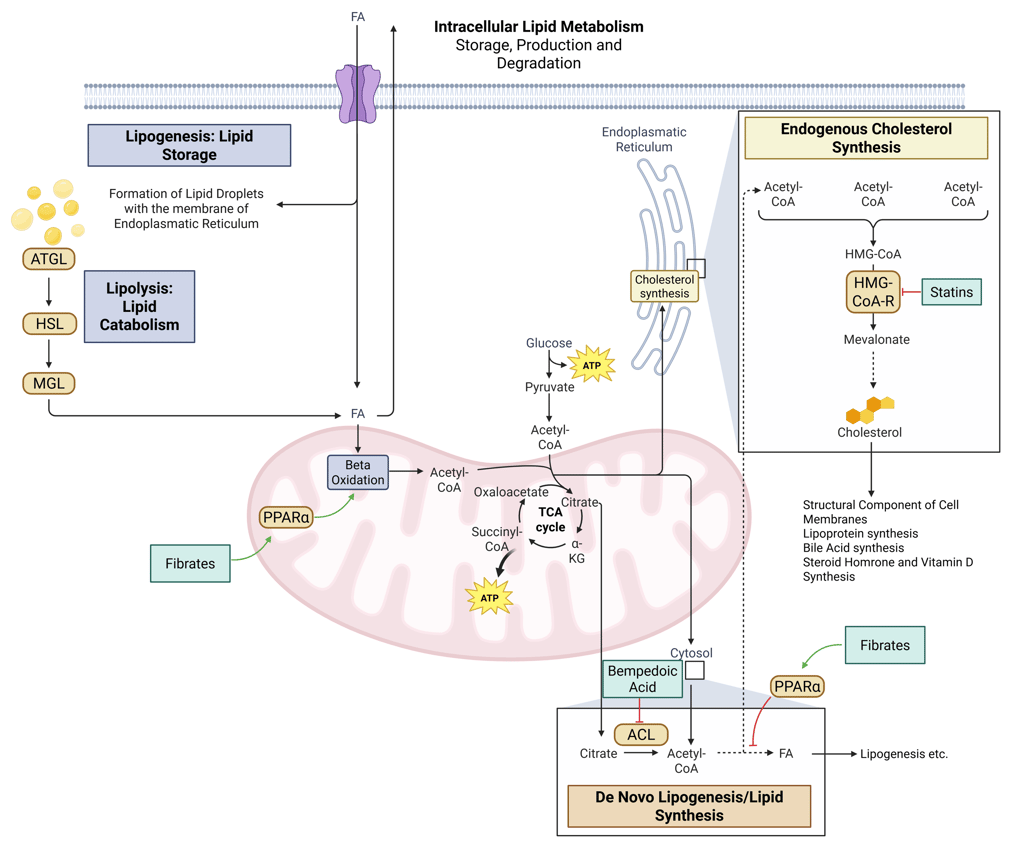

Detailed Illustration of intracellular Lipid Metabolism. HMG-CoA-R: HMG-CoA-Reductase, ATGL: Adipose Triglyceride Lipase, HSL: Hormone Sensitive Lipase, MGL: Monoglyceride Lipase, FA: Fatty Acids, ACL: ATP-Citrate-Lyase

The solution will be provided at the end of the clinical pearl. First, we are going to highlight each treatment options including their clinical implications in detail.

Management of dyslipidemia relies on a combination of lifestyle interventions and pharmacological therapies. The decision to initiate drug treatment, as well as the choice and intensity of therapy, is guided by the individual patient’s risk for lipid-related complications, including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and pancreatitis. In patients at elevated risk, pharmacological therapy is often introduced concurrently with lifestyle modification rather than sequentially.

Because lipid-lowering agents differ substantially in their mechanisms of action, selection of a specific therapy should be tailored to the underlying lipid abnormality and informed by practical considerations such as patient preferences, drug availability, regulatory approval, and reimbursement constraints. In the following sections, the mechanisms of action of the major therapeutic classes used in dyslipidemia will be reviewed and contextualized to illustrate how physiological targeting translates into clinical lipid profile improvement.

Lifestyle Modification

Lifestyle modification, particularly structured exercise and targeted dietary changes, forms the cornerstone of dyslipidemia management and is endorsed as first-line therapy by major professional societies, including the Endocrine Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

Regular physical activity, encompassing both aerobic exercise and resistance training, produces modest yet clinically meaningful improvements in circulating lipids. Aerobic or combined exercise programs typically reduce LDL-C, total cholesterol, and triglycerides by roughly 3–12%, while increasing HDL-C by approximately 2–3 mg/dL. These effects scale with training intensity, session duration, and long-term adherence.

Dietary modification also affects lipid parameters. According to the American College of Cardiology, replacing saturated with unsaturated fats and limiting dietary cholesterol can lower LDL-C concentrations by about 10–15%. Interventions targeting triglyceride levels, such as carbohydrate restriction, weight reduction, and limiting added sugars and alcohol, can yield triglyceride reductions in the range of 16–42%, with the largest improvements observed in individuals achieving substantial weight loss or adhering to very-low-carbohydrate diets.

Pharmacological Agents Primarily Targeting Cholesterol Reduction

Inhibition of Hepatic Cholesterol Synthesis

Statins

Statins reduce circulating cholesterol concentrations by competitively inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in hepatic cholesterol synthesis. Suppression of endogenous cholesterol production lowers intracellular cholesterol content within hepatocytes, which in turn activates sterol regulatory element–binding protein 2 (SREBP-2). This transcriptional response leads to increased expression of LDL receptor genes and a higher density of LDL receptors on the hepatocyte surface. Enhanced receptor-mediated uptake of LDL particles from the circulation results in a pronounced reduction in plasma LDL cholesterol levels.

Illustration: How Statins influence intracellular Lipid Metabolism. HMG-CoA-R: HMG-CoA-Reductase, ATGL: Adipose Triglyceride Lipase, HSL: Hormone Sensitive Lipase, MGL: Monoglyceride Lipase, FA: Fatty Acids, ACL: ATP-Citrate-Lyase

Illustration: How Statins influence the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor

Bempedoic Acid

Bempedoic acid is an orally administered, once-daily prodrug that is selectively activated in hepatocytes. Its active metabolite inhibits ATP-citrate lyase, an enzyme positioned upstream of HMG-CoA reductase in the hepatic cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. By reducing intracellular cholesterol availability in the liver, bempedoic acid induces upregulation of LDL receptor expression, thereby enhancing receptor-mediated clearance of LDL particles from the circulation and lowering plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations.

Illustration: How Bempedoic Acid influences intracellular Lipid Metabolism. HMG-CoA-R: HMG-CoA-Reductase, ATGL: Adipose Triglyceride Lipase, HSL: Hormone Sensitive Lipase, MGL: Monoglyceride Lipase, FA: Fatty Acids, ACL: ATP-Citrate-Lyase

Modulation of the PCSK9–LDL Receptor Axis

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is predominantly synthesized in the liver and plays a central role in regulating LDL receptor (LDLR) turnover. By binding to LDLRs on the hepatocyte surface, PCSK9 directs the receptor–ligand complex toward lysosomal degradation, thereby reducing the number of LDLRs available for clearance of circulating LDL cholesterol.

PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies

PCSK9 inhibitors, including alirocumab and evolocumab, are monoclonal antibodies administered subcutaneously that bind circulating PCSK9 and prevent its interaction with LDLRs. By blocking PCSK9-mediated receptor degradation, these agents preserve LDLR expression on the hepatocyte surface, leading to enhanced receptor-mediated uptake of LDL particles from plasma and marked reductions in LDL-C levels. In addition to LDL-C lowering, PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies reduce apolipoprotein B and lipoprotein(a) concentrations. While pleiotropic anti-inflammatory or anti-atherosclerotic effects have been proposed, their primary therapeutic action remains augmentation of LDLR availability and LDL-C clearance.

Inclisiran

Inclisiran lowers LDL cholesterol by suppressing hepatic PCSK9 production through RNA interference. It consists of a synthetic small interfering RNA (siRNA) conjugated to N-acetylgalactosamine, enabling selective uptake by hepatocytes via asialoglycoprotein receptors. Following cellular entry, the guide strand of inclisiran is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex, which binds PCSK9 mRNA and promotes its degradation. This post-transcriptional silencing prevents PCSK9 protein synthesis, resulting in sustained reductions in circulating PCSK9 levels, preservation of LDL receptors, and enhanced clearance of LDL cholesterol.

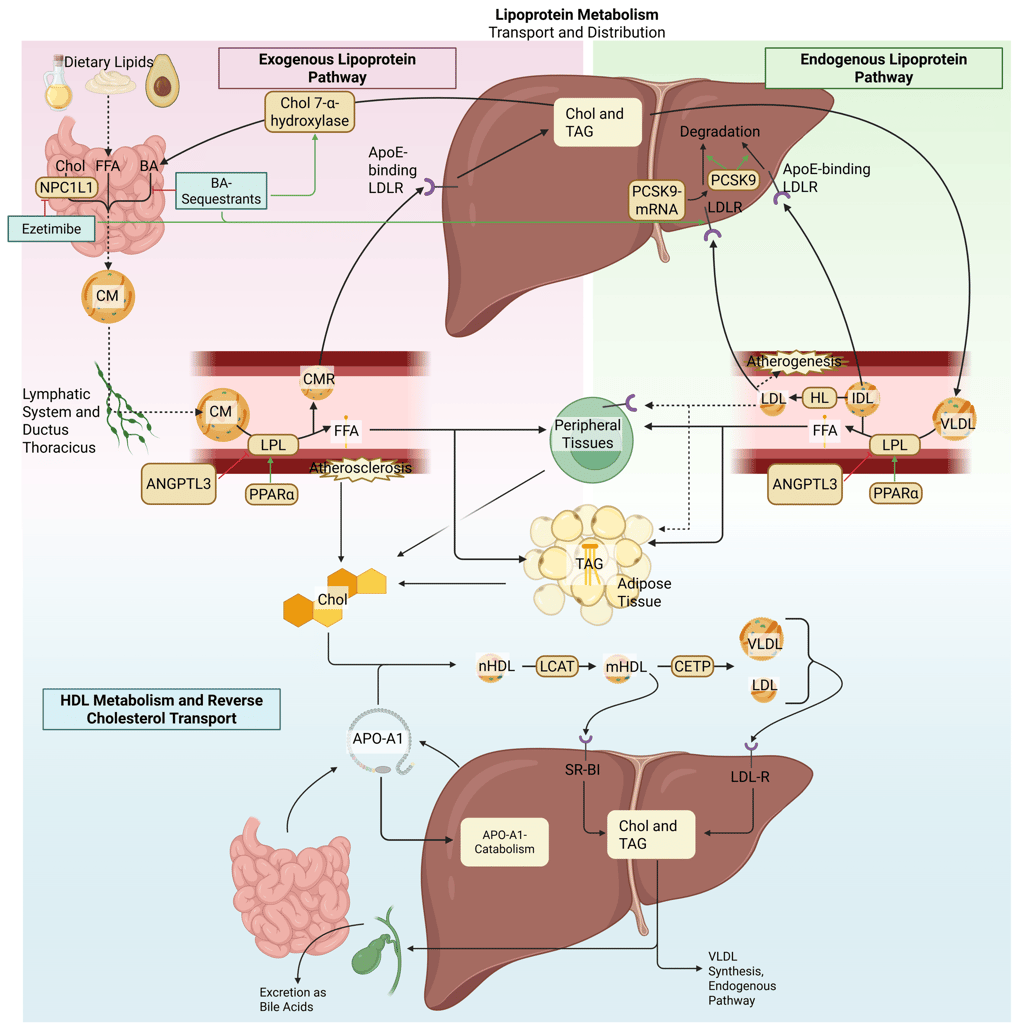

Illustration: How PCSK9 Modulators influence the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor. Note: PCSK9-inhibiting antibodies bind on the LDL-R on the cell surface. Due to illusrative reasons, the mechanism of action is illustrated within the liver.

Intestinal Cholesterol-Uptake Inhibitors

Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe reduces cholesterol absorption at the level of the intestinal brush border by targeting the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) transporter. NPC1L1 is a multipass transmembrane protein on the apical surface of enterocytes that mediates the uptake of both dietary and biliary cholesterol. By binding to NPC1L1 and preventing the conformational changes required for its endocytosis, ezetimibe effectively blocks cholesterol entry into the enterocyte. As a result, less cholesterol is delivered to the liver, leading to a compensatory decline in hepatic cholesterol stores. This reduction triggers upregulation of LDL receptor expression, thereby enhancing the clearance of LDL particles from the circulation.

Bile acid sequestrants

Bile acid sequestrants (e.g., cholestyramine, colesevelam) exert their effect by binding bile acids within the intestinal lumen, thereby preventing their reabsorption in the distal ileum and disrupting the enterohepatic circulation. Loss of bile acids prompts the liver to increase bile acid synthesis, primarily through upregulation of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway. The heightened demand for cholesterol drives increased hepatic LDL receptor expression, resulting in greater removal of LDL cholesterol from plasma. These agents act locally in the gut and are not systemically absorbed.

Illustration: How gastrointestinal cholesterol uptake inhibitors influence the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor.

Pharmacological Agents Primarily Targeting Triglyceride Reduction

Modulator of Lipoprotein Lipase Activity

Fibrates

Fibrates exert their lipid-modifying effects primarily through activation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha (PPARα), a nuclear receptor that regulates the transcription of genes central to lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. PPARα activation increases expression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), thereby enhancing the intravascular hydrolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, including very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and chylomicrons. This mechanism results in a marked reduction in plasma triglyceride concentration. In parallel, fibrates reduce hepatic production of apolipoprotein C-III, an endogenous inhibitor of LPL, further facilitating triglyceride clearance. Additional effects include decreased hepatic VLDL secretion, mediated by increased fatty acid β-oxidation and reduced de novo lipogenesis. Collectively, these actions lower circulating triglycerides and remnant lipoproteins.

Illustration: How Fibrates influence the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor.

Illustration: How Fibrates influence intracellular Lipid Metabolism. HMG-CoA-R: HMG-CoA-Reductase, ATGL: Adipose Triglyceride Lipase, HSL: Hormone Sensitive Lipase, MGL: Monoglyceride Lipase, FA: Fatty Acids, ACL: ATP-Citrate-Lyase

Inhibitors of Hepatic VLDL Production

Omega-3 fatty acids

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), lower plasma triglyceride concentrations predominantly by attenuating hepatic VLDL-triglyceride synthesis. This reduction is achieved through decreased availability of triglyceride substrates and downregulation of genes involved in lipogenesis. In addition, omega-3 fatty acids may modestly enhance the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, potentially through increased lipoprotein lipase–mediated hydrolysis. Collectively, these effects result in a clinically meaningful reduction in circulating triglyceride levels.

Niacin (nicotinic acid)

Niacin primarily modulates lipid metabolism by suppressing hepatic triglyceride synthesis and subsequent very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion. This effect is mediated in part through inhibition of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2, a key enzyme involved in triglyceride assembly within hepatocytes. Reduced VLDL output leads to downstream decreases in circulating VLDL and LDL cholesterol concentrations. In addition, niacin favorably influences high-density lipoprotein metabolism by diminishing hepatic clearance of apolipoprotein A-I, thereby extending HDL particle residence time and increasing HDL-C levels. This mechanism supports enhanced reverse cholesterol transport.

Illustration: How VLDL-Inhibitors influence the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor.

Pharmacological Agents Targeting Triglyceride and Cholesterol Reduction

Modulator of Lipoprotein Lipase Activity

ANGPTL3 inhibitors

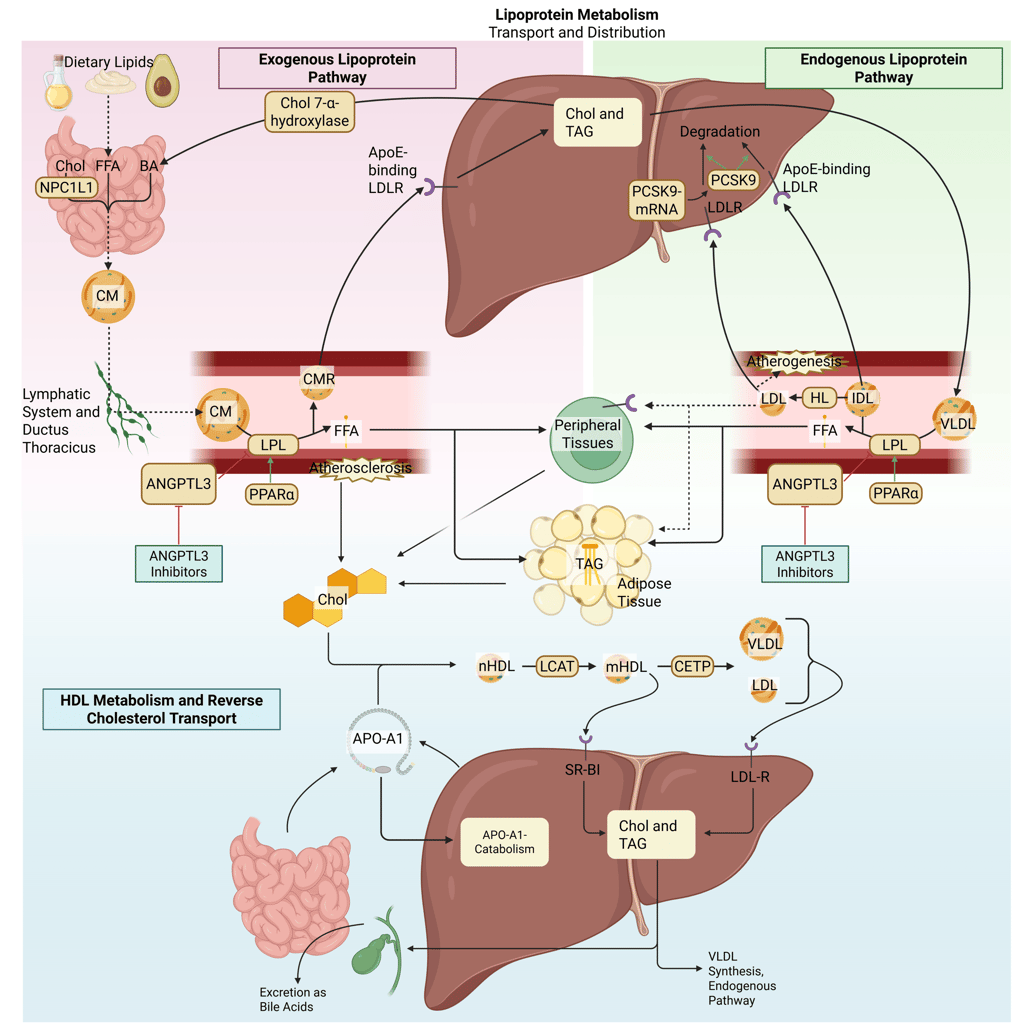

Angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) is a hepatically derived regulator of lipid metabolism that suppresses the activity of both lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase, often in coordination with ANGPTL8. This inhibition promotes accumulation of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and contributes to elevations in plasma triglycerides and LDL cholesterol. Pharmacological inhibition of ANGPTL3, achieved through monoclonal antibodies, antisense oligonucleotides, or small interfering RNA, releases this brake on lipase activity. The resulting increase in LPL function accelerates the clearance of VLDL, chylomicrons, and their remnants, leading to substantial reductions in plasma triglycerides, remnant cholesterol, and decreases in LDL-C. Importantly, LDL-C lowering via ANGPTL3 inhibition occurs independently of the LDL receptor pathway, rendering this approach particularly relevant for patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia.

Illustration: How ANGPTL3-Inhibitors influence the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor.

Concluding Remarks: Translating Lipid Pathophysiology into Clinical Practice and Solution to the Exercise at the beginning of the Clinical Pearl

Understanding the physiology and pathophysiology of lipid metabolism is essential for selecting the most appropriate treatment strategy for dyslipidemia. Lipid abnormalities arise from distinct disturbances in cholesterol synthesis, intestinal absorption, lipoprotein production, clearance, and intravascular remodeling, and each therapeutic class targets a specific component of these pathways. Knowledge of where a dysregulation occurs allows clinicians to align lifestyle interventions and pharmacological therapies with the dominant lipid abnormality, such as elevated LDL cholesterol, hypertriglyceridemia, or mixed dyslipidemia, thereby maximizing efficacy while minimizing unnecessary exposure to ineffective treatments. Moreover, mechanistic insight helps anticipate treatment limitations, adverse effects, and drug interactions, and supports rational combination therapy in high-risk patients. Ultimately, a physiology-based approach enables individualized, evidence-informed management of dyslipidemia and optimizes cardiovascular risk reduction.

Detailed Illustration of the lipoprotein metabolism with mechanism of action of the most important pharmacological agents to treat dyslipidemia. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor. Note: PCSK9-inhibiting antibodies bind on the LDL-R on the cell surface. Due to illusrative reasons, the mechanism of action is illustrated within the liver.

Detailed Illustration of intracellular Lipid Metabolism with mechanism of action of the most important pharmacological agents to treat dyslipidemia. HMG-CoA-R: HMG-CoA-Reductase, ATGL: Adipose Triglyceride Lipase, HSL: Hormone Sensitive Lipase, MGL: Monoglyceride Lipase, FA: Fatty Acids, ACL: ATP-Citrate-Lyase

References

All Illustrations were created in https://BioRender.com

Balasubramanian, Rajkapoor, und Naina M. P. Maideen. 2021. „HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors (Statins) and Their Drug Interactions Involving CYP Enzymes, P-Glycoprotein and OATP Transporters-An Overview“. Current Drug Metabolism 22 (5): 328–41. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200222666210114122729.

Berberich, Amanda J, und Robert A Hegele. 2022. „A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia“. Endocrine Reviews 43 (4): 611–53. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab037.

Bergeron, Nathalie, Binh An P. Phan, Yunchen Ding, Aleyna Fong, und Ronald M. Krauss. 2015. „Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibition: A New Therapeutic Mechanism for Reducing Cardiovascular Disease Risk“. Circulation 132 (17): 1648–66. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016080.

Berglund, Lars, John D. Brunzell, Anne C. Goldberg, u. a. 2012. „Evaluation and Treatment of Hypertriglyceridemia: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline“. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 97 (9): 2969–89. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-3213.

„DailyMed - NIACIN tablet, film coated, extended release“. o. J. Zugegriffen 22. Dezember 2025. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8e290f96-e8c6-47fd-863f-1c9480f28d9b.

Davidson, Michael H., Annemarie Armani, James M. McKenney, und Terry A. Jacobson. 2007. „Safety Considerations with Fibrate Therapy“. The American Journal of Cardiology 99 (6A): 3C-18C. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.016.

Jellinger, Paul S., Yehuda Handelsman, Paul D. Rosenblit, u. a. 2017. „American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Guidelines for Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease“. Endocrine Practice 23 (April): 1–87. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP171764.APPGL.

„Lipid Management in Patients with Endocrine Disorders: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline | The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism | Oxford Academic“. o. J. Zugegriffen 10. Dezember 2025. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/105/12/3613/5909161.

Lloyd-Jones, Donald M., Pamela B. Morris, Christie M. Ballantyne, u. a. 2022. „2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 80 (14): 1366–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006.

Marston, Nicholas A., und André Zimerman. 2025. „Future of Angiopoietin-like Protein 3 Inhibitors as a Therapeutic Agent“. Current Opinion in Lipidology 36 (6): 285–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0000000000001013.

Merćep, Iveta, Dominik Strikić, Ana Marija Slišković, und Željko Reiner. 2022. „New Therapeutic Approaches in Treatment of Dyslipidaemia-A Narrative Review“. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 15 (7): 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15070839.

Michos, Erin D., John W. McEvoy, und Roger S. Blumenthal. 2019. „Lipid Management for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease“. New England Journal of Medicine 381 (16): 1557–67. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1806939.

Mourikis, Philipp, Saif Zako, Lisa Dannenberg, u. a. 2020. „Lipid Lowering Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease: From Myth to Molecular Reality“. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 213 (September): 107592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107592.

Noel, Zachary R., und Craig J. Beavers. 2017. „Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitors: A Brief Overview“. The American Journal of Medicine 130 (2): 229.e1-229.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.09.021.

Patel, Shailendra B., Kathleen L. Wyne, Samina Afreen, u. a. 2025. „American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacologic Management of Adults With Dyslipidemia“. Endocrine Practice 31 (2): 236–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2024.09.016.

Ray, Kausik K., Pablo Corral, Enrique Morales, und Stephen J. Nicholls. 2019. „Pharmacological Lipid-Modification Therapies for Prevention of Ischaemic Heart Disease: Current and Future Options“. Lancet (London, England) 394 (10199): 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31950-6.

Seidah, Nabil G., Gaetan Mayer, Ahmed Zaid, u. a. 2008. „The Activation and Physiological Functions of the Proprotein Convertases“. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 40 (6–7): 1111–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.030.

Sirtori, Cesare R., Shizuya Yamashita, Maria Francesca Greco, Alberto Corsini, Gerald F. Watts, und Massimiliano Ruscica. 2020. „Recent Advances in Synthetic Pharmacotherapies for Dyslipidaemias“. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 27 (15): 1576–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319845314.

Smart, Neil A., David Downes, Tom van der Touw, u. a. 2025. „The Effect of Exercise Training on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis“. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 55 (1): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02115-z.

Smart, Neil A., Gina N. Wood, Melissa J. Pearson, Gudrun Dieberg, Tom van der Touw, und Karam Kostner. 2025. „Exercise Training for the Management of Dyslipidaemia. A Position Statement from Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA)“. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, November 11, S1440-2440(25)00487-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2025.11.004.

Staels, B., J. Dallongeville, J. Auwerx, K. Schoonjans, E. Leitersdorf, und J. C. Fruchart. 1998. „Mechanism of Action of Fibrates on Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism“. Circulation 98 (19): 2088–93. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.98.19.2088.

„Statin Safety and Associated Adverse Events: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association | Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology“. o. J. Zugegriffen 22. Dezember 2025. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073?rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed&url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org.

Toth, Peter P. 2010. „Drug Treatment of Hyperlipidaemia: A Guide to the Rational Use of Lipid-Lowering Drugs“. Drugs 70 (11): 1363–79. https://doi.org/10.2165/10898610-000000000-00000.

Urban, Daniel, Janine Pöss, Michael Böhm, und Ulrich Laufs. 2013. „Targeting the Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 for the Treatment of Dyslipidemia and Atherosclerosis“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62 (16): 1401–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.056.

Virani, Salim S., Pamela B. Morris, Anandita Agarwala, u. a. 2021. „2021 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Management of ASCVD Risk Reduction in Patients With Persistent Hypertriglyceridemia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 78 (9): 960–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.06.011.

Wright, R. Scott, Kausik K. Ray, Frederick J. Raal, u. a. 2021. „Pooled Patient-Level Analysis of Inclisiran Trials in Patients With Familial Hypercholesterolemia or Atherosclerosis“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 77 (9): 1182–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.058.

Zhan, Shipeng, Min Tang, Fang Liu, Peiyuan Xia, Maoqin Shu, und Xiaojiao Wu. 2018. „Ezetimibe for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality Events“. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11 (11): CD012502. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012502.pub2.

© 2025 EndoCases. All rights reserved.

This platform is intended for medical professionals, particularly endocrinology residents, and is provided for educational purposes only. It supports learning and clinical reasoning but is not a substitute for professional medical advice or patient care. The information is general in nature and should be applied with appropriate clinical judgment and in accordance with local guidelines.

Portions of the text on this website were edited with the assistance of Artificial Intelligence to improve grammar and phrasing, as English is not my first language. All medical content, ideas for illustrations, and overall structure are original and based on the author’s own expertise and the cited medical literature. No AI tools were used to generate or influence the educational content itself.

All of the content is independent of my employer.

Use of this site implies acceptance of our Terms of Use

Contact us via E-Mail: contact@endo-cases.com