From Lipid Physiology to the Laboratory Test: Understanding What We Measure

Lipid measurements are a fundamental component of the endocrine and metabolic workup in many patients, including those with dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypothyroidism, and hypogonadism. In clinical practice, their main applications lie in evaluating lipid disorders, both as primary diseases and as secondary manifestations of underlying endocrine or metabolic dysfunction, and in assessing cardiovascular risk as part of comprehensive risk stratification.

Accurate interpretation of lipid profiles requires more than familiarity with reference ranges; it demands a solid understanding of lipid physiology, including how lipoproteins are synthesized, transported, and metabolized, as well as intracellular lipid metabolism. This physiological insight enables clinicians to connect laboratory findings with underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, guide targeted therapy, and provide meaningful counseling to patients.

Core Elements of Lipid Physiology

Lipids, specifically fatty acids and cholesterol, play essential roles in the human body as structural components of cell membranes, energy sources, and precursors for bioactive molecules. As they are inherently insoluble in water, their transport through the bloodstream necessitates the association with specific proteins (Apolipoproteins), to form lipoproteins. These complexes play a central role in lipid metabolism, facilitating the transport of dietary lipids from the small intestine to the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue, the transfer of hepatic lipids to peripheral tissues, and the reverse transport of cholesterol from peripheral tissues back to the liver and intestine.

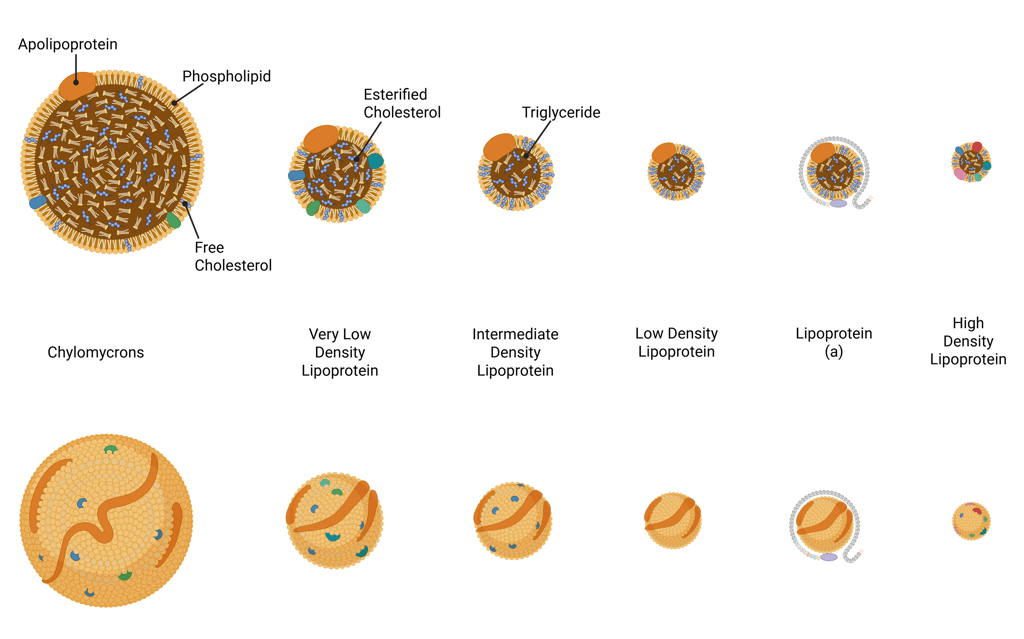

Lipoprotein Structure

Lipoproteins consist of a hydrophilic surface layer composed of phospholipids, free cholesterol, and apolipoproteins, which encase a hydrophobic core containing cholesteryl esters and triglycerides. Based on size, lipid, and apolipoprotein composition, lipoproteins are classified into different classes: chylomicrons, VLDL, IDL, LDL, HDL, and lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)).

Illustration of Lipoproteins

Chylomicrons are large, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins synthesized by intestinal enterocytes after the ingestion of dietary fat. They are the largest lipoprotein particles (approximately 75–450 nm in diameter) and rich in triglycerides. Their primary role is to transport dietary lipids, including triglycerides, cholesterol, and fat-soluble vitamins—from the intestine into the lymphatic circulation and subsequently the systemic bloodstream, where they deliver these lipids to peripheral tissues for storage or energy utilization.

Very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) is a triglyceride-rich, apoB-containing lipoprotein secreted by the liver. Both VLDL and its remnants are pro-atherogenic.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is derived from the metabolism of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and are cleared from circulation mainly via hepatic LDL receptors. They are the primary vehicles for delivering cholesterol from the liver to peripheral tissues.

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) are characterized by their small size (8–12 nm diameter) and high density. they are the key component inreverse cholesterol transport (see below). It is the only, non-atherogenic lipoprotein.

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is an apoB-containing lipoprotein, similar to LDL-C distinguished by the presence of a unique apolipoprotein(a) component. It is also pro-atherogenic, Lp(a) synthesis is genetically determined.

Apolipoproteins and Their Roles

Apolipoproteins are integral to the structure and function of lipoproteins, playing essential roles in lipid transport and metabolism. They fulfill four essential functions:

Guiding the synthesis and assembly of lipoproteins

Providing structural stability to lipoprotein particles

Acting as ligands for specific lipoprotein receptors

Activating or inhibiting enzymes involved in lipoprotein metabolism

Each class of lipoprotein has a characteristic apolipoprotein composition that determines its metabolic fate and interactions with enzymes and receptors. There are at least 18 different types of apolipoproteins identified in human plasma. The diverse functions of apolipoproteins can be illustrated by apolipoprotein E (ApoE). It is synthesized primarily in the liver and intestine, though it is also produced in several extrahepatic tissues, including the brain, spleen, and macrophages. Apo E associates with chylomicrons, chylomicron remnants, VLDL, IDL, and a subset of HDL particles, and can exchange dynamically between lipoprotein classes.

Apo E plays a central role in lipoprotein clearance by serving as a ligand for the LDL receptor and LDL receptor–related protein 1 (LRP-1), facilitating the hepatic uptake of Apo E–containing remnant particles such as chylomicron and VLDL remnants.

Key Enzymes and Transfer Proteins in Lipid Metabolism

Several key enzymes and transfer proteins coordinate the movement and modification of lipids between lipoprotein particles, thereby maintaining lipid homeostasis. The most important among these are Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL), Hepatic Lipase, Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein (CETP) and Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT). The following sections outline the key physiological roles of these proteins and enzymes. Detailed aspects of lipid metabolism will be addressed subsequently.

Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is synthesized primarily in skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and adipose tissue, then secreted and anchored to the capillary endothelium. It hydrolyzes the triglycerides contained in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (namely chylomicrons and VLDL) releasing free fatty acids that are taken up by muscle cells for energy or by adipocytes for storage. As triglycerides are removed, chylomicrons are converted to chylomicron remnants, and VLDL to IDL (VLDL remnants).

Hepatic lipase, produced by the liver and localized to the sinusoidal surface of hepatocytes, catalyzes the hydrolysis of triglycerides and phospholipids in IDL and LDL, generating smaller, denser lipoprotein particles (IDL is converted to LDL, and large LDL to small LDL). It also acts on HDL particles, promoting their remodeling by converting large HDL into smaller HDL subfractions.

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), present in the plasma, facilitates the exchange of lipids between lipoprotein classes. CETP mediates the transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL to VLDL, chylomicrons, and LDL, while reciprocally transferring triglycerides from these particles back to HDL. This bidirectional lipid exchange plays a pivotal role in reverse cholesterol transport and in determining the composition and size of circulating lipoproteins.

Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is essential for the esterification of free cholesterol in plasma, a key step in HDL maturation and reverse cholesterol transport.

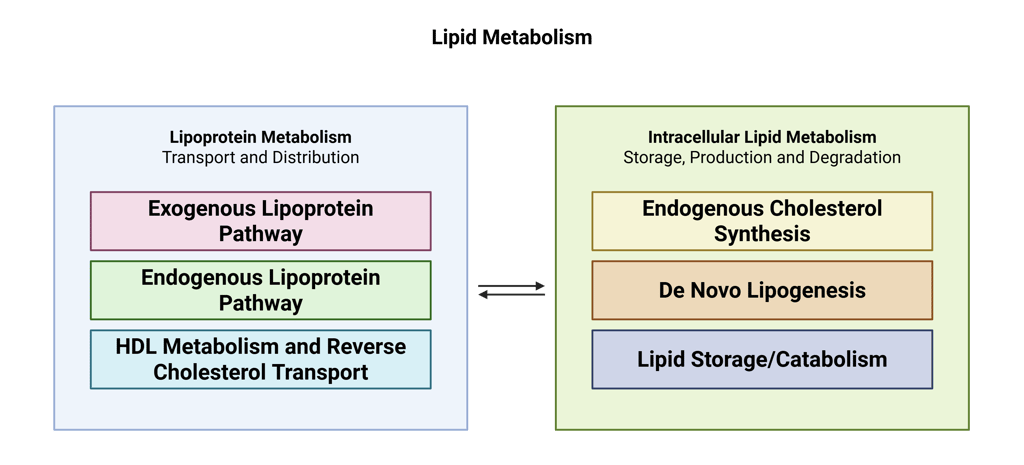

Lipid Metabolism

Lipid metabolism can be understood as comprising two interdependent components. The first is lipoprotein metabolism, which governs the transport and distribution of lipids between the liver, intestine, and peripheral tissues. The second is intracellular lipid metabolism, encompassing the synthesis, storage, and breakdown of lipids to provide energy locally within cells or to supply distant tissues. These two facets are tightly linked, as intracellular lipid processes generate substrates that enter the circulation via lipoproteins, while circulating lipids influence cellular lipid handling.

Lipoprotein Metabolism

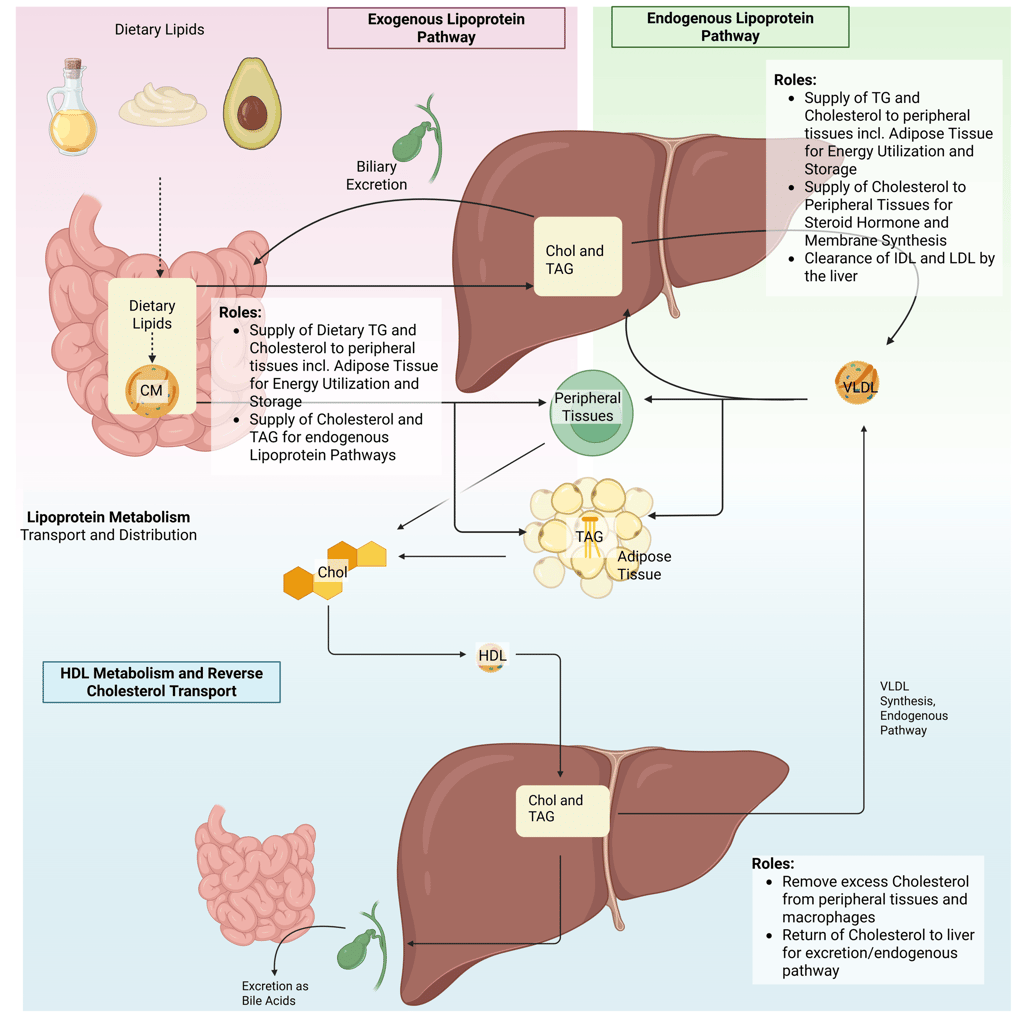

Lipoprotein metabolism can be divided into three main pathways—the exogenous pathway, the endogenous pathway, and reverse cholesterol transport—each serving distinct roles in lipid handling and energy homeostasis.

1. Exogenous Pathway

Transports dietary triglycerides and cholesterol from the intestine to muscle and adipose tissue for energy utilization and storage, bypassing the hepatic portal system.

Provides substrates for the endogenous lipoprotein pathway, supporting subsequent lipid transport and metabolism.

2. Endogenous Pathway

Delivers triglycerides to muscle and adipose tissue to supply energy and maintain energy storage.

Distributes cholesterol for essential cellular functions, including membrane synthesis and steroid hormone production.

Maintains plasma lipid homeostasis through regulated clearance of remnant lipoproteins and LDL particles via hepatic receptors.

3. Reverse Cholesterol Transport

Removes excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues, including macrophages within arterial walls, and transports it back to the liver for excretion into bile, playing a key role in atherosclerosis prevention.

The illustration below depicts the key components of the three major lipoprotein pathways. In the sections that follow, we will examine each pathway in greater detail.

Overview of the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, , VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein

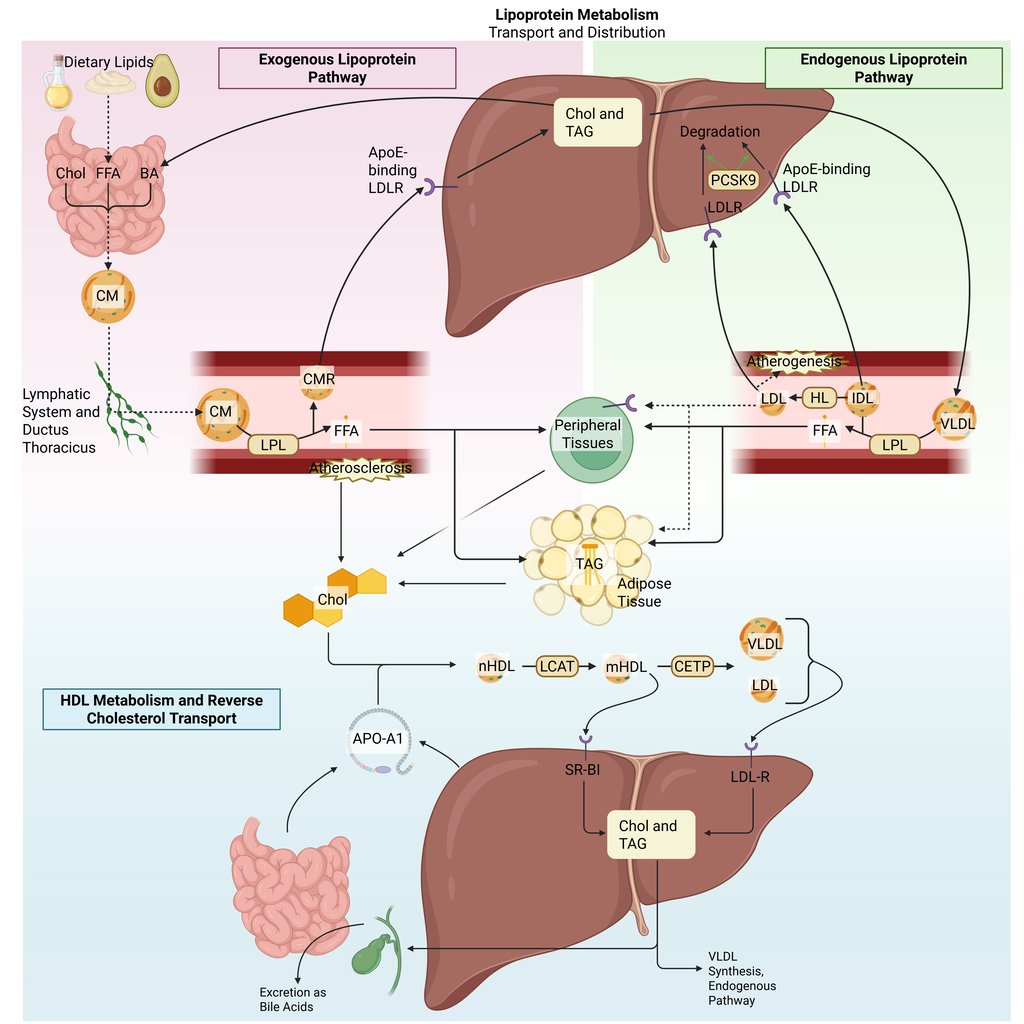

Endogenous Lipoprotein Pathway

The exogenous lipoprotein pathway originates in the small intestine. Although the precise mechanisms of free fatty acid absorption remain incompletely understood, they likely involve both passive diffusion and specialized transporters. Within intestinal enterocytes, triglycerides and cholesteryl esters are assembled into chylomicrons in the endoplasmic reticulum. These chylomicrons are secreted into the lymphatic system and enter the systemic circulation through the thoracic duct, thereby bypassing the liver in the initial phase.

Once in circulation, lipoprotein lipase (LPL)—produced by muscle and adipose tissue—is anchored to the capillary endothelium, where it hydrolyzes the triglycerides contained in chylomicrons. As triglycerides are progressively removed, the chylomicrons decrease in size and become chylomicron remnants, which are enriched in cholesteryl esters and acquire Apo E.

The liver plays a central role in clearing chylomicron remnants from the bloodstream. Apo E on the remnant surface binds to hepatic LDL receptors and related receptors to mediate uptake. Through this coordinated process, the exogenous pathway efficiently transports dietary triglycerides to muscle and adipose tissue for energy utilization and storage. In individuals with normal lipid metabolism, it can move more than 100 g of dietary fat per day without causing substantial elevations in plasma triglyceride levels. Dietary cholesterol, on the other hand, is primarily delivered to the liver, where it may be incorporated into VLDL, converted into bile acids, or secreted back into the intestine via the biliary pathway.

Endogenous Lipoprotein Pathway

In the liver, cholesterol and triglycerides are packaged with newly synthesized Apo B-100 in the endoplasmic reticulum, a process analogous to chylomicron assembly in the intestine, resulting in the formation of VLDL particles. Once in circulation, the triglycerides within VLDL are hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in peripheral tissues, releasing fatty acids, a mechanism very similar to that of chylomicrons. VLDL and chylomicrons compete for LPL-mediated clearance, and as triglycerides are removed from VLDL, VLDL remnants (IDL) enriched in cholesteryl esters are formed. These remnants are cleared by the liver through binding of Apo E to LDL and LRP-1 receptors, mirroring the pathway for chylomicron remnant uptake. Unlike chylomicron remnants, which are largely and rapidly removed from circulation, only about half of VLDL remnants are cleared, though this proportion can vary. The remaining triglycerides in VLDL remnants are further hydrolyzed by hepatic lipase, producing LDL particles that are primarily composed of cholesteryl esters and Apo B-100, with most triglycerides removed and exchangeable apolipoproteins transferred to other lipoproteins. Consequently, the metabolism of VLDL is a key pathway for LDL formation, and the plasma LDL concentration is largely determined by the number of hepatic LDL receptors, which regulate both LDL production and clearance.

Reverse Cholesterol Transport

Reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) is the process by which the body removes excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues, including macrophages within arterial walls.

It begins with the synthesis of apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), the principal structural and functional protein of HDL, in the liver and intestine. Once secreted, ApoA-I interacts with cholesterol and phospholipids released from hepatocytes and enterocytes, initiating the formation of nascent HDL particles. These particles are further metabolized by the Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) to form mature HDL particles.

Cholesteryl esters carried by HDL are cleared through two principal routes: (1) direct hepatic uptake, or (2) transfer to apoB-containing lipoproteins (e.g., LDL, VLDL) mediated by cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), with subsequent hepatic removal of these particles.

Ultimately, cholesterol reaching the liver is secreted into bile and eliminated from the body through the feces. Importantly, the efficiency of RCT, particularly the cholesterol efflux capacity of macrophages, has been shown to correlate more closely with reduced atherosclerotic risk than static HDL cholesterol concentrations alone. HDL metabolism is a dynamic and multifaceted process involving synthesis, remodeling, and catabolism, and its antiatherogenic properties depend not only on HDL quantity but also on its functional quality.

Detailed Illustration of the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicrone Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor

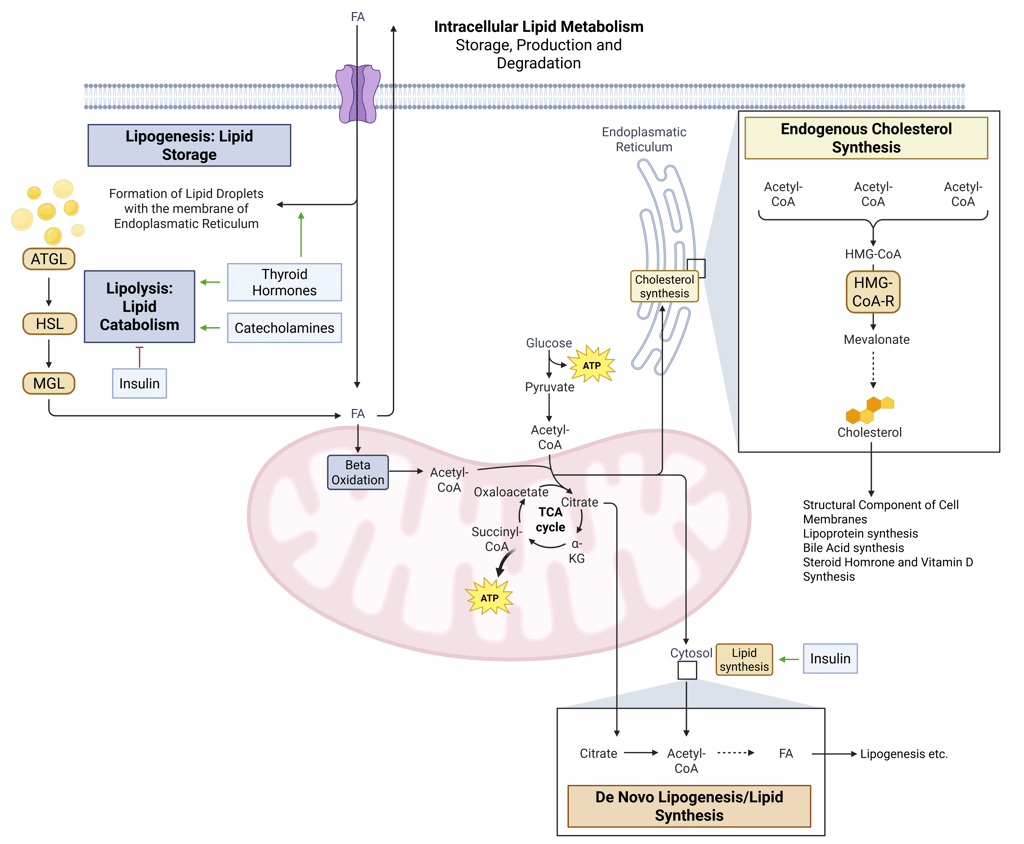

Intracellular Lipid Metabolism

Once fatty acids reach hepatocytes or peripheral tissues such as adipose tissue and muscle, they are directed into distinct metabolic pathways depending on the cell’s energy status and substrate requirements.

Lipogenesis: Lipid Storage. Within cells, lipids are stored as neutral lipids, primarily triacylglycerols and steryl esters, inside specialized organelles known as lipid droplets (LDs). These droplets originate from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the site of neutral lipid synthesis, and serve as dynamic reservoirs that buffer energy supply and membrane lipid availability.

Lipolysis: Lipid Catabolism. During fasting, exercise, or other catabolic states, lipolysis breaks down triacylglycerols within lipid droplets through a coordinated series of enzymatic reactions, releasing free fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol. FFAs are then mobilized to peripheral tissues or to the intracellular mitochondira for energy production, while glycerol serves as a substrate for gluconeogenesis in the liver.

Fatty acid oxidation: Within mitochondria, β-oxidation converts fatty acids into acetyl-CoA, NADH, and FADH₂, fueling the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP. This process is especially critical during fasting and prolonged exercise when glucose availability is limited.

Cholesterol synthesis: Cholesterol is synthesized predominantly in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes through a multistep pathway beginning with the condensation of acetyl-CoA units. The rate-limiting step, the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate by HMG-CoA reductase, is tightly regulated by hormonal and nutritional signals. Cholesterol serves as a structural component of cell membranes, modulating membrane integrity and signaling, and acts as the precursor for steroid hormones, bile acids, and vitamin D, linking lipid metabolism to multiple endocrine functions.

De novo lipogenesis (DNL): DNL converts excess acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates into fatty acids, primarily within the liver and adipose tissue. This pathway is strongly stimulated by insulin and high-carbohydrate intake, contributing to triglyceride synthesis and hepatic fat accumulation in states of energy surplus.

Detailed Illustration of intracellular Lipid Metabolism. HMG-CoA-R: HMG-CoA-Reductase, ATGL: Adipose Triglyceride Lipase, HSL: Hormone Sensitive Lipase, MGL: Monoglyceride Lipase, FA: FAtty Acids

How Lipid Physiology Translates to Clinical Practice

In this section, we will explore how lipid physiology translates into daily clinical practice. A thorough understanding of lipid physiology transforms routine laboratory results into meaningful clinical insights. It enables clinicians to connect measured lipid parameters with underlying mechanisms, recognize disease patterns, and tailor patient-specific management strategies. The core clinical applications of lipid physiology include:

Rational selection and timing of lipid measurements

Interpretation of lipid patterns in the context of pathophysiology

Recognition of endocrine influences on lipid metabolism

Identification of primary and secondary causes of dyslipidemia (e.g., genetic disorders, liver or renal disease, medication effects)

Guidance for individualized therapeutic strategies (e.g., statins for LDL-C, fibrates for TG, PCSK9 inhibitors for severe familial hypercholesterolemia)

Integration into cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention (e.g., use of ApoB, non–HDL-C, or Lp(a) for refined risk stratification)

Rational selection and timing of lipid measurements

Understanding lipid metabolism helps determine what to measure and when. The most widely used laboratory parameters to evaluate the lipid metabolism include:

Standard Lipid Profile

Lipoprotein(a): Lp(a)

Apolipoprotein B: Apo-B

A standard lipid profile typically includes total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides. These measurements are central to cardiovascular risk assessment and are also routinely used in the evaluation of renal or hepatic disease, pancreatitis, diabetes, and other endocrine disorders.

The measured triglyceride concentration reflects the triglyceride content within circulating lipoproteins such as chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), and their remnants. Because chylomicron and remnant levels fluctuate postprandially, fasting samples may be helpful when triglyceride quantification is clinically relevant.

In contrast, HDL-C and LDL-C levels are generally stable regardless of recent food intake, making non-fasting lipid profiles adequate for most routine clinical evaluations.

LDL Cholesterol Measurement

It is crucial to understand how LDL-C values are derived.

In most laboratories, LDL-C is calculated using the Friedewald formula based on total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglycerides. However, this formula underestimates LDL-C in cases of marked hypertriglyceridemia.

When triglycerides are elevated, direct LDL-C measurement using homogeneous chemical or immunologic assays is recommended—these are increasingly standard in modern endocrinology and lipidology practice.

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB)

Measurement of ApoB provides an estimate of the total number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles, including VLDL, IDL, LDL, and Lp(a).

According to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines, ApoB measurement is particularly useful in patients with triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL, where it may more accurately reflect atherogenic burden than LDL-C or non–HDL-C alone.

Lipoprotein(a)

Lipoprotein(a) is a genetically determined, independent, and causal risk factor for both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and calcific aortic valve stenosis. Its contribution to cardiovascular risk is additive to that of LDL-C.

The American Heart Association recommends measuring Lp(a) at least once in a lifetime, particularly in individuals with a family history of premature ASCVD or those at high cardiovascular risk.

Interpretation of lipid patterns in the context of pathophysiology

Each lipid profile provides insight into the underlying pathogenic process.

The main determinant of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration is the activity of hepatic LDL receptors (LDLR), which mediate the uptake and clearance of LDL particles from plasma.

LDLR activity is influenced by genetic variation, dietary composition, and hormonal regulation.

Chronic elevations in LDL-C are most frequently due to polygenic reductions in LDL receptor activity, but can also reflect secondary causes such as nephrotic syndrome, or cholestasis. In contrast to LDL-C-elevation due to genetic disorders (familial hypercholesterinemia), LDL-C-elevations are typically less pronounced in the above mentioned situations.

Genetic Dyslipidemias

Inherited mutations in genes encoding key apolipoproteins, receptors, or enzymes can produce characteristic lipid abnormalities.

Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia (Type III hyperlipoproteinemia) results from mutations in Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) that impair hepatic recognition of chylomicron and VLDL remnants via the LDL receptor, leading to elevated total cholesterol and triglycerides.

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), the most common monogenic lipid disorder, is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the LDL receptor (LDLR), ApoB, or PCSK9, resulting in markedly elevated LDL-C and premature atherosclerosis.

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) deficiency leads to markedly elevated HDL cholesterol (hyperalphalipoproteinemia), with large, cholesteryl ester-rich HDL particles and small, triglyceride-rich LDL particles.

Lipoprotein lipase deficiency causes severe hypertriglyceridemia and accumulation of chylomicrons.

LCAT deficiency leads to low HDL Cholesterol

Recognition of endocrine influences on lipid metabolism

The endocrine system plays a central role in regulating lipid metabolism at multiple levels — from lipid synthesis and storage to mobilization and clearance. Hormones act as metabolic coordinators, aligning lipid handling with nutritional state, energy demand, and physiological stress. Consequently, endocrine dysfunctions frequently manifest as characteristic lipid abnormalities, which can serve as valuable diagnostic and prognostic clues.

Insulin Deficiency and Resistance

Insulin is a key anabolic hormone that regulates both carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.

Under normal conditions, insulin suppresses adipose tissue lipolysis and activates lipoprotein lipase (LPL), promoting triglyceride clearance from circulating VLDL and chylomicrons.

In states of insulin deficiency (e.g., type 1 diabetes mellitus) or insulin resistance (e.g., metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus), these regulatory effects are impaired.

The resulting increase in lipolysis releases excess free fatty acids (FFAs) into the circulation, which are taken up by the liver and drive hepatic VLDL overproduction.

Simultaneously, reduced LPL activity limits the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, leading to hypertriglyceridemia.

Hypothyroidism

Thyroid hormones exert wide-ranging effects on lipid metabolism, influencing synthesis, transport, and degradation of lipids.

They upregulate key enzymes such as HMG-CoA reductase, cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), hepatic lipase, and lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), and they enhance expression of both LDL receptors and HDL receptor SR-BI on hepatocytes.

Deficiency of thyroid hormone therefore results in reduced LDL receptor activity, impaired cholesterol clearance, and decreased HDL remodeling.

The typical lipid profile in overt hypothyroidism includes elevated total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides, with low or normal HDL-C levels. Even subclinical hypothyroidism can modestly raise LDL-C, highlighting the close interplay between thyroid function and lipid metabolism.

Identification of primary and secondary causes of dyslipidemia

A mechanistic understanding of lipid pathways helps clinicians navigate complex lipid abnormalities. Primary (genetic) disorders such as familial hypercholesterolemia (defective LDL receptor) result in predictable lipid profiles. Secondary causes, including chronic kidney disease, liver dysfunction, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, and medications (e.g., corticosteroids, retinoids, antiretrovirals), alter lipid levels via distinct mechanisms.

By recognizing these patterns, clinicians can avoid misclassification, order appropriate confirmatory tests, and target the root cause.

Guidance for individualized therapeutic strategies

Therapy selection is guided by both lipid profile and underlying physiology. Elevated triglycerydes can be targeted through lifestyle and Fibrate, which lead to increased expression of lipoprotein lipase, leading to enhanced catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.

Statins, on the other hand, remain the first-line therapy for LDL-C reduction by competitively inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. Reduced intracellular cholesterol levels trigger upregulation of LDL receptors (LDL-R) on hepatocyte surfaces, enhancing clearance of circulating LDL particles and thereby reducing plasma LDL-C concentrations.

PCSK9 inhibitors prevent LDL receptor degradation, and are therefore key therapies genetic LDL-C-elevation.

References

All Illustrations were Created in https://BioRender.com

Avramoglu, Rita Kohen, Heather Basciano, und Khosrow Adeli. „Lipid and Lipoprotein Dysregulation in Insulin Resistant States“. Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry 368, Nr. 1–2 (Juni 2006): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.026.

Bays, Harold Edward, Carol F. Kirkpatrick, Kevin C. Maki, Peter P. Toth, Ryan T. Morgan, Justin Tondt, Sandra Michelle Christensen, Dave L. Dixon, und Terry A. Jacobson. „Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: A joint expert review from the Obesity Medicine Association and the National Lipid Association 2024“. Journal of Clinical Lipidology 18, Nr. 3 (1. Mai 2024): e320–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2024.04.001.

Berberich, Amanda J., und Robert A. Hegele. „A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia“. Endocrine Reviews 43, Nr. 4 (13. Juli 2022): 611–53. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab037.

Feingold, Kenneth R. „Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism“. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, Lipids: Update on Diagnosis and Management of Dyslipidemia, 51, Nr. 3 (1. September 2022): 437–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2022.02.008.

Grundy, Scott M., Neil J. Stone, Alison L. Bailey, Craig Beam, Kim K. Birtcher, Roger S. Blumenthal, Lynne T. Braun, u. a. „2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 73, Nr. 24 (25. Juni 2019): e285–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003.

Houten, Sander M., Sara Violante, Fatima V. Ventura, und Ronald J. A. Wanders. „The Biochemistry and Physiology of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation and Its Genetic Disorders“. Annual Review of Physiology 78 (2016): 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105045.

Jonklaas, Jacqueline. „Hypothyroidism, lipids, and lipidomics“. Endocrine 84, Nr. 2 (2024): 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-023-03420-9.

„Lipid Management in Patients with Endocrine Disorders: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline | The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism | Oxford Academic“. Zugegriffen 3. November 2025. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/105/12/3613/5909161.

Martin, Seth S., Michael J. Blaha, Mohamed B. Elshazly, Eliot A. Brinton, Peter P. Toth, John W. McEvoy, Parag H. Joshi, u. a. „Friedewald-Estimated versus Directly Measured Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Treatment Implications“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62, Nr. 8 (20. August 2013): 732–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.079.

Ray, Kausik K., Pablo Corral, Enrique Morales, und Stephen J. Nicholls. „Pharmacological Lipid-Modification Therapies for Prevention of Ischaemic Heart Disease: Current and Future Options“. Lancet (London, England) 394, Nr. 10199 (24. August 2019): 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31950-6.

Recazens, Emeline, Etienne Mouisel, und Dominique Langin. „Hormone-sensitive lipase: sixty years later“. Progress in Lipid Research 82 (1. April 2021): 101084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2020.101084.

Stellaard, Frans, Sabine Baumgartner, Ronald Mensink, Bjorn Winkens, Jogchum Plat, und Dieter Lütjohann. „Serum Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Concentration Is Not Dependent on Cholesterol Synthesis and Absorption in Healthy Humans“. Nutrients 14, Nr. 24 (17. Dezember 2022): 5370. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245370.

Wang, Yuhui, Jose Viscarra, Sun-Joong Kim, und Hei Sook Sul. „Transcriptional Regulation of Hepatic Lipogenesis“. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 16, Nr. 11 (November 2015): 678–89. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm4074.

Yang, Alexander, und Emilio P. Mottillo. „Adipocyte Lipolysis: From Molecular Mechanisms of Regulation to Disease and Therapeutics“. The Biochemical Journal 477, Nr. 5 (13. März 2020): 985–1008. https://doi.org/10.1042/BCJ20190468.

© 2025 EndoCases. All rights reserved.

This platform is intended for medical professionals, particularly endocrinology residents, and is provided for educational purposes only. It supports learning and clinical reasoning but is not a substitute for professional medical advice or patient care. The information is general in nature and should be applied with appropriate clinical judgment and in accordance with local guidelines.

Portions of the text on this website were edited with the assistance of Artificial Intelligence to improve grammar and phrasing, as English is not my first language. All medical content, ideas for illustrations, and overall structure are original and based on the author’s own expertise and the cited medical literature. No AI tools were used to generate or influence the educational content itself.

All of the content is independent of my employer.

Use of this site implies acceptance of our Terms of Use

Contact us via E-Mail: contact@endo-cases.com