Biochemical Signatures of Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas: How they link to Tumor Origin and Genetics

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PPGLs) are neuroendocrine tumors derived from chromaffin tissue, arising within the adrenal medulla in the case of pheochromocytomas, or along sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia for paragangliomas. Their clinical presentation is diverse and may include classic catecholamine-related symptoms, detection as an incidental imaging finding, or evaluation in the setting of known hereditary risk.

Biochemical evaluation remains central to the diagnostic work-up of PPGLs and is essential for distinguishing secreting from non-secreting paragangliomas. Current guidelines consistently identify plasma free metanephrines (metanephrine, normetanephrine and methoxytyramine) or urinary fractionated metanephrines as the most sensitive and specific assays for detecting these tumors. In contrast, older markers such as VMA and HVA are no longer recommended, as their diagnostic accuracy is markedly inferior to that of metanephrine-based testing.

While exceptions always exist, typical biochemical profiles can already suggest whether a tumor originates from the adrenal medulla, extra-adrenal sympathetic chain, or, the usually parasympathetic, head-and-neck region, and may even hint at underlying genetic drivers.

To illustrate this, consider the following three typical biochemical profiles. Try to match each one to the most likely tumor type:

an adrenal pheochromocytoma

a sympathetic paraganglioma

a paraganglioma located in the head & neck area

The solution will be displayed at the end of the clinical pearl. In the next section, we will explore why these biochemical signatures emerge, how they relate to tumor origin, and what they can reveal about potential genetic alterations.

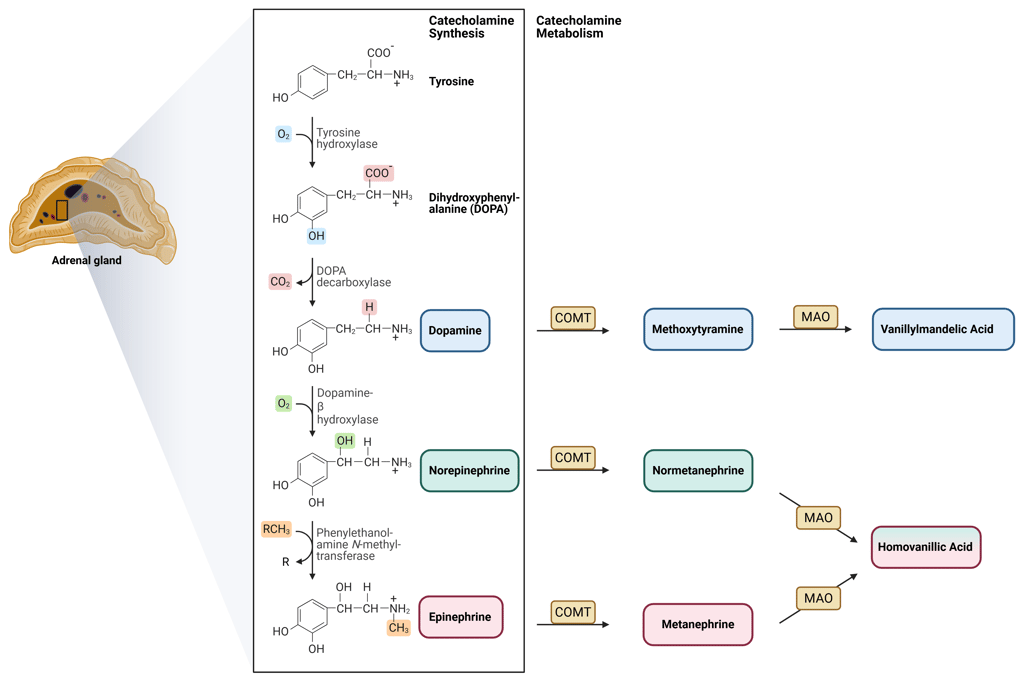

Catecholamine Synthesis and Metabolism

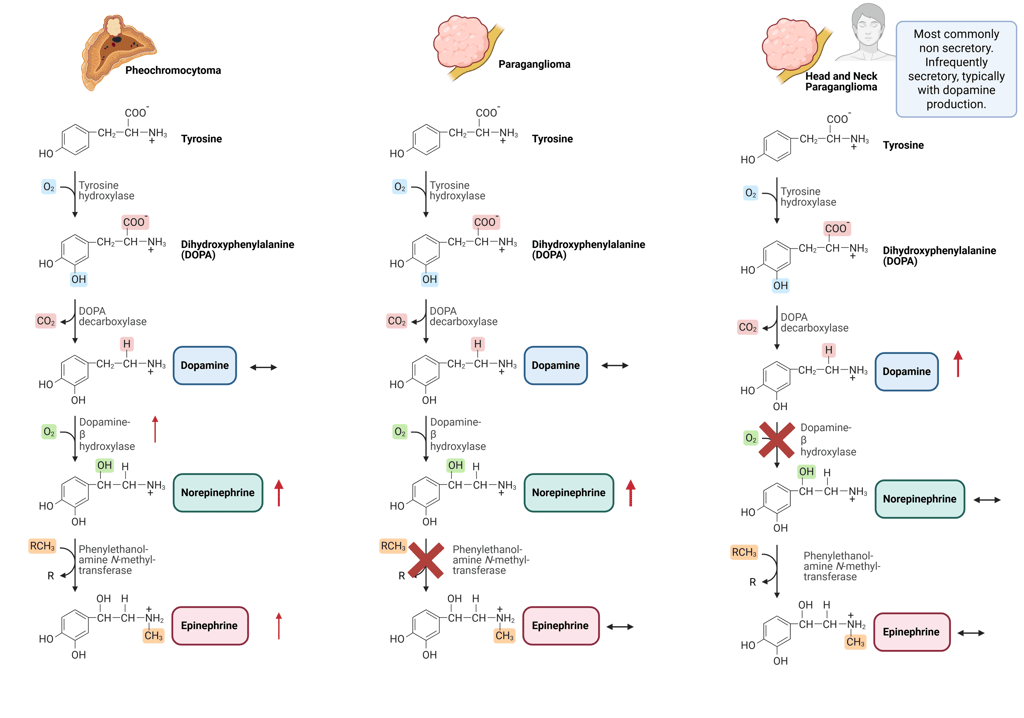

Catecholamine synthesis is a multi-step process that requires several specific enzymes. It begins with tyrosine, which is converted to DOPA by tyrosine hydroxylase. DOPA is then decarboxylated to form dopamine via DOPA decarboxylase. Dopamine can subsequently be hydroxylated to norepinephrine through the action of dopamine β-hydroxylase. The final step, the conversion of norepinephrine to epinephrine, depends on phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), which catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group to norepinephrine.

The characteristic catecholamine profiles observed in different tumor types reflect the pattern of enzyme expression within the tumor. This pattern, in turn, is determined by the tissue of origin and the genetic drivers underlying the tumor.

Epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine are primarily metabolized by the enzymes monoamine oxidase (MAO) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). COMT catalyzes the O-methylation of the catechol ring, converting dopamine into 3-methoxytyramine, norepinephrine into normetanephrine, and epinephrine into metanephrine. These metabolites are subsequently further processed to form vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and homovanillic acid (HVA), which represent the major urinary end products of catecholamine metabolism.

Illustration of catecholamine synthesis and metabolization

This Illustration was created from Endo-Cases in https://BioRender.com based on a submitted template by Purves et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Ed. Oxford University Press

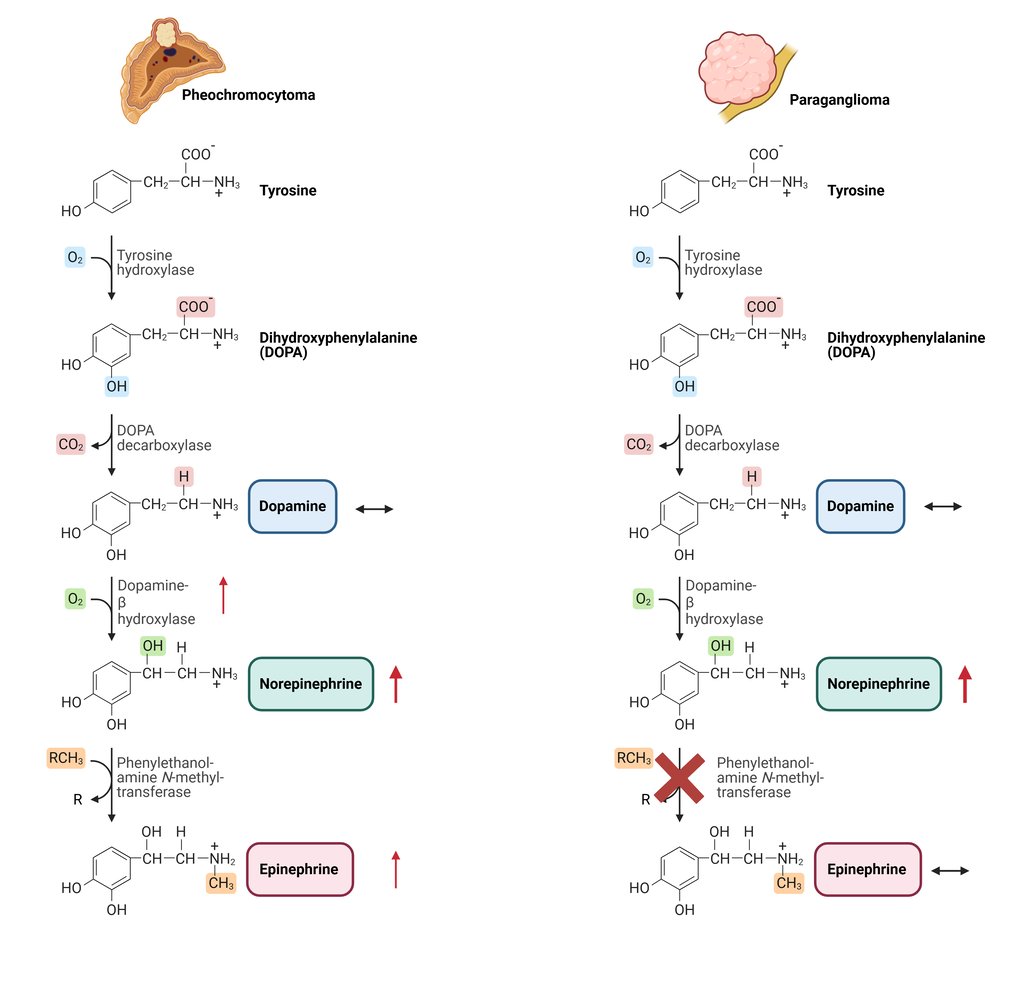

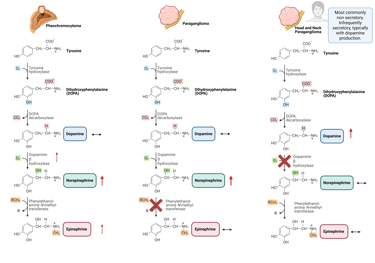

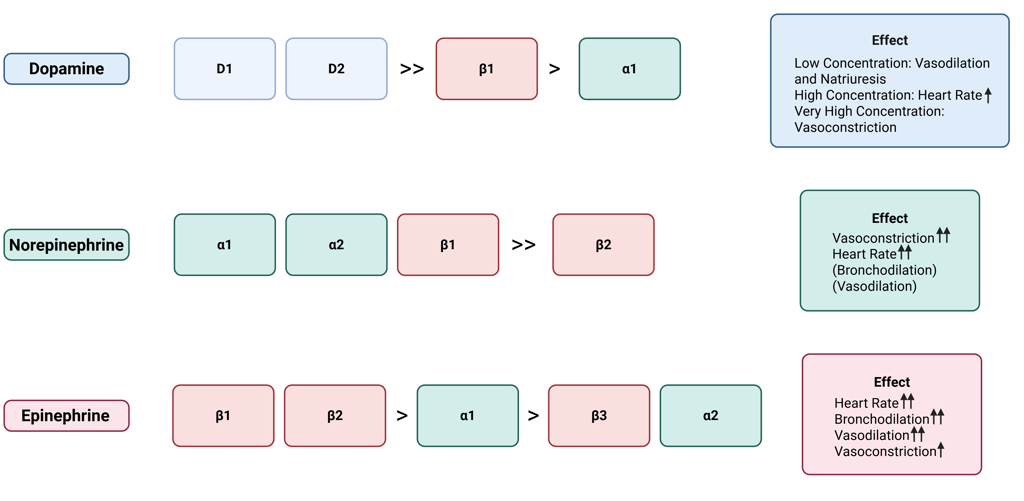

Tissue Origin

Pheochromocytomas, originating from the adrenal medulla, typically have intact enzyme expression and therefore produce both norepinephrine and epinephrine, which is reflected by elevated levels of normetanephrine and metanephrine. In contrast, sympathetic paragangliomas, arising from extra-adrenal sites, primarily secrete norepinephrine, resulting in a predominance of normetanephrine. These tumors rarely generate significant amounts of epinephrine, due to low or absent expression of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), the enzyme required for its synthesis.

Illustration of typical catecholamine synthesis and patterns of Pheochromocytomas and sympathetic Paragangliomas

This Illustration was created from Endo-Cases in https://BioRender.com based on a submitted template by Purves et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Ed. Oxford University Press

Head and neck paragangliomas typically arise from parasympathetic paraganglia, which normally do not synthesize substantial amounts of norepinephrine or epinephrine. This feature is reflected in their biochemical profile, as they rarely secrete catecholamines. When catecholamine production occurs, dopamine is more commonly released. The production of dopamine is supported by expression of the early enzymes in the catecholamine biosynthetic pathway, including tyrosine hydroxylase and aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, whereas dopamine β-hydroxylase, required for conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine, is typically absent or expressed at low levels, resulting in elevated dopamine and it’s metabolite methoxytyramine and normal/low normetanephrine and metanephrine.

Illustration of typical catecholamine synthesis and patterns of Pheochromocytomas, sympathetic and head and neck Paragangliomas

This Illustration was created from Endo-Cases in https://BioRender.com based on a submitted template by Purves et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Ed. Oxford University Press

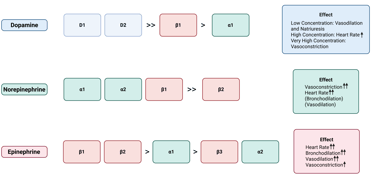

At low concentrations, dopamine mainly engages D1- and D2-like receptors, resulting in vasodilation and increased sodium excretion, especially in the renal and splanchnic vascular beds. When present at moderate to high levels, dopamine also stimulates β1-adrenergic receptors, which increases heart rate and cardiac contractility. At very high concentrations, it activates α1-adrenergic receptors, causing vasoconstriction and a rise in blood pressure.

Head and neck paragangliomas that secrete dopamine are generally clinically silent, because dopamine has much lower activity at adrenergic receptors compared with norepinephrine and epinephrine. Furthermore, dopamine is rapidly metabolized, preventing it from reaching systemic levels sufficient to produce the classic symptoms of catecholamine excess. For more information about clinical manifestation of catecholamine excess see this Clinical Pearl.

Illustration of Catecholamine, their affinity to dopamine and adrenergic receptors and resulting effects

It should be emphasized that, although biochemical profiles can provide hints regarding tumor localization, their clinical utility is limited, as catecholamine patterns alone cannot consistently distinguish between different tumor types.

Genetic Alterations

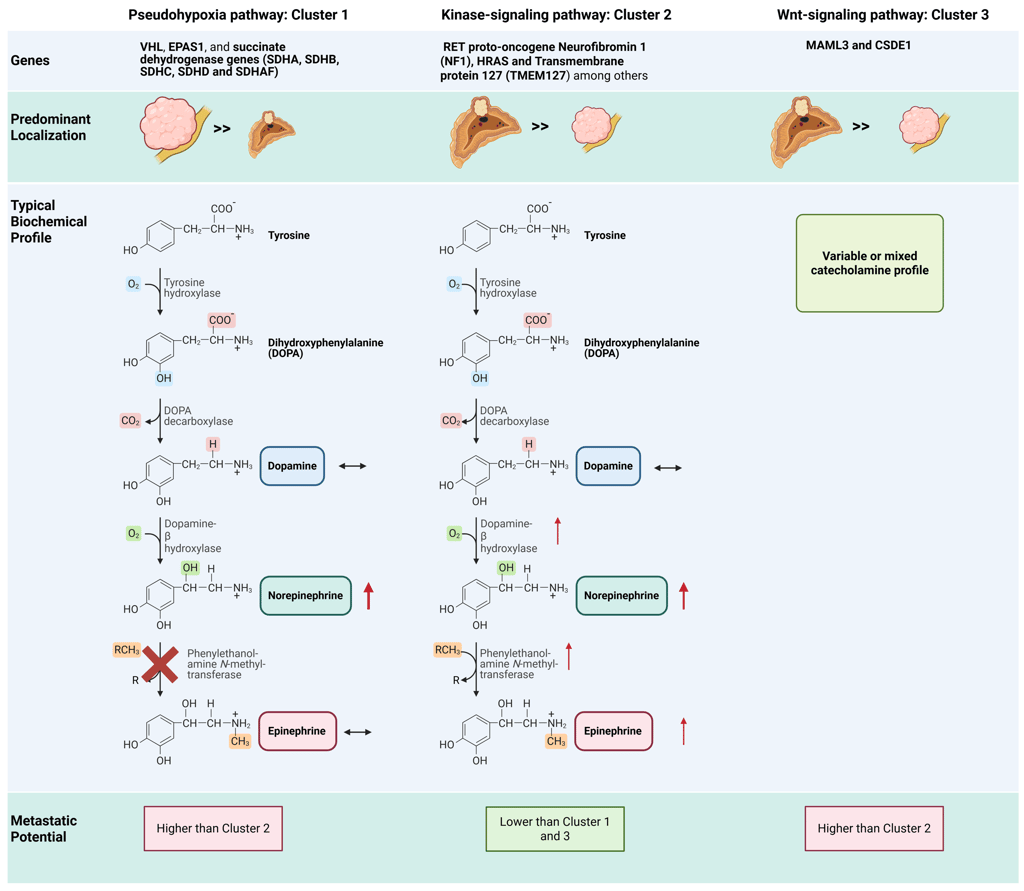

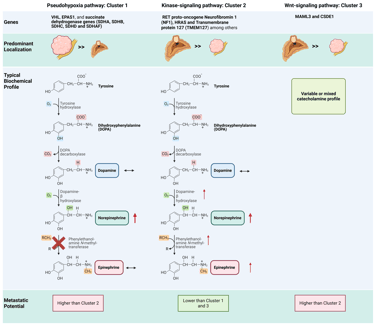

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas exhibit the highest heritability among all tumor types. Together, germline and somatic mutations in over 20 known PPGL driver genes are found in approximately 70% of Caucasian patients. These genetic alterations are classified into three main molecular clusters: pseudohypoxia cluster 1 (subdivided into 1A and 1B), kinase-signaling cluster 2, and Wnt signaling cluster 3.

Advances in genetic profiling have facilitated the identification of distinct clinical, biochemical, and imaging phenotypes, enabling more personalized approaches to PPGL diagnosis, treatment, and long-term follow-up. In this section, we will focus on how these molecular clusters correlate with the biochemical patterns of catecholamine secretion.

Cluster 1 tumors (pseudohypoxia pathway), which include those associated with Krebs cycle–related genes, VHL, EPAS1, and succinate dehydrogenase (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD and SDHAF) are predominantly extra-adrenal (exept VHL-associated tumors) and typically exhibit a noradrenergic biochemical phenotype. This pattern arises from low or absent expression of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), the enzyme responsible for converting norepinephrine to epinephrine. PNMT expression is suppressed by pseudohypoxic signaling driven by these mutations. Patients with cluster 1 tumors require close surveillance due to an increased risk of recurrence and metastasis.

In contrast, cluster 2 tumors (kinase-signaling pathway) are most often adrenal in location and display an adrenergic phenotype associated with episodic symptoms. Affected genes include the RET proto-oncogene as well as genes encoding for neurofibromin 1 (NF1), HRAS and transmembrane protein 127 (TMEM127). These tumors generally follow a less aggressive course and maintain high expression of the catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes, particularly PNMT and dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH). This intact enzymatic machinery enables efficient conversion of norepinephrine to epinephrine, leading to substantial secretion of both catecholamines.

The clinical characteristics of cluster 3 tumors (Wnt signaling pathway) are less well defined, although aggressive behavior appears likely. Biochemically, these tumors exhibit variable or mixed catecholamine secretion patterns, without a consistent predominance of norepinephrine or epinephrine. Expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes, including PNMT and DBH, is generally preserved but not markedly elevated or suppressed.

Illustration cluster dependent features: Note: The illustration depicts the general or typical predominant features; individual variation and differences within each group may occur. Some characteristics, such as the metastatic potential associated with specific genetic alterations, are based on limited data due to the rarity of these tumors.

This Illustration was created from Endo-Cases in https://BioRender.com based on a submitted template by Purves et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Ed. Oxford University Press

Not all pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas can be fully classified within the established molecular cluster system. This may result from the absence of known driver mutations, the presence of rare or novel genetic alterations, or incomplete molecular characterization. Some tumors display mixed or atypical molecular features, and ongoing advances in molecular profiling continue to identify new subtypes.

While the molecular cluster of a pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma can often be inferred from clinical characteristics (tumor location, catecholamine secretion pattern, and metastatic behavior) a definitive classification and optimal management require molecular profiling. Such profiling informs the selection of appropriate biochemical assays, imaging strategies, genetic counseling, and surveillance protocols. Consequently, genetic testing is recommended for all patients with pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma.

Based on the biochemical profiles presented at the beginning of this clinical pearl, the most likely corresponding diagnoses are as follows:

References

All Illustrations were created in https://BioRender.com

„Adrenal Disorders“. 2021. In Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Pediatric Disease. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817962-8.00008-1.

Bucolo, Claudio, Gian Marco Leggio, Filippo Drago, und Salvatore Salomone. 2019. „Dopamine Outside the Brain: The Eye, Cardiovascular System and Endocrine Pancreas“. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 203 (November): 107392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.07.003.

„Catecholamine Metabolism - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics“. o. J. Zugegriffen 17. November 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/catecholamine-metabolism.

„Catecholamines and Blood Pressure Regulation“. 2023. In Endocrine Hypertension. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-96120-2.00010-8.

Crona, Joakim, Margareta Nordling, Rajani Maharjan, u. a. 2014. „Integrative Genetic Characterization and Phenotype Correlations in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Tumours“. PloS One 9 (1): e86756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086756.

Crona, Joakim, David Taïeb, und Karel Pacak. 2017. „New Perspectives on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Toward a Molecular Classification“. Endocrine Reviews 38 (6): 489–515. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2017-00062.

Eisenhofer, G., M. M. Walther, T. T. Huynh, u. a. 2001. „Pheochromocytomas in von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome and Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 Display Distinct Biochemical and Clinical Phenotypes“. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 86 (5): 1999–2008. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.5.7496.

Eisenhofer, Graeme, Christina Pamporaki, und Jacques W. M. Lenders. 2023. „Biochemical Assessment of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma“. Endocrine Reviews 44 (5): 862–909. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnad011.

Foo, S. H., S. P. Chan, V. Ananda, und V. Rajasingam. 2010. „Dopamine-Secreting Phaeochromocytomas and Paragangliomas: Clinical Features and Management“. Singapore Medical Journal 51 (5): e89-93.

Goldstein, David S., Genessis Castillo, Patti Sullivan, und Yehonatan Sharabi. 2021. „Differential Susceptibilities of Catecholamines to Metabolism by Monoamine Oxidases“. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 379 (3): 253–59. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.121.000826.

Gupta, Garima, Karel Pacak, und AACE Adrenal Scientific Committee. 2017. „PRECISION MEDICINE: AN UPDATE ON GENOTYPE/BIOCHEMICAL PHENOTYPE RELATIONSHIPS IN PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA/PARAGANGLIOMA PATIENTS“. Endocrine Practice: Official Journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 23 (6): 690–704. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP161718.RA.

Kaplinsky, Anna, Reut Halperin, Gadi Shlomai, und Amit Tirosh. 2024. „Role of Epigenetic Regulation on Catecholamine Synthesis in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma“. Cancer 130 (19): 3289–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.35426.

Missale, C., S. R. Nash, S. W. Robinson, M. Jaber, und M. G. Caron. 1998. „Dopamine Receptors: From Structure to Function“. Physiological Reviews 78 (1): 189–225. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189.

Neumann, Hartmut P. H., William F. Young, und Charis Eng. 2019. „Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma“. The New England Journal of Medicine 381 (6): 552–65. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1806651.

Nölting, Svenja, Nicole Bechmann, David Taieb, u. a. 2022. „Personalized Management of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma“. Endocrine Reviews 43 (2): 199–239. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab019.

Osinga, Thamara E., Esther Korpershoek, Ronald R. de Krijger, u. a. 2015. „Catecholamine-Synthesizing Enzymes Are Expressed in Parasympathetic Head and Neck Paraganglioma Tissue“. Neuroendocrinology 101 (4): 289–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000377703.

Pihlblad, Vincent E. D., Jan Calissendorff, und Henrik Falhammar. 2025. „Differences in Clinical Presentation Between Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas“. Clinical Endocrinology 103 (5): 651–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.70002.

Sasaki, Yuriko, Maki Kanzawa, Masaaki Yamamoto, u. a. 2024. „Composite Paraganglioma-Ganglioneuroma with Atypical Catecholamine Profile and Phenylethanolamine N-Methyltransferase Expression: A Case Report and Literature Review“. Endocrine Journal 71 (1): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.EJ23-0271.

Shah, Manisha H., Whitney S. Goldner, Al B. Benson, u. a. 2021. „Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology“. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN 19 (7): 839–68. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2021.0032.

Purves et al. (2018) Neuroscience. 6th Ed. Oxford University Press

© 2025 EndoCases. All rights reserved.

This platform is intended for medical professionals, particularly endocrinology residents, and is provided for educational purposes only. It supports learning and clinical reasoning but is not a substitute for professional medical advice or patient care. The information is general in nature and should be applied with appropriate clinical judgment and in accordance with local guidelines.

Portions of the text on this website were edited with the assistance of Artificial Intelligence to improve grammar and phrasing, as English is not my first language. All medical content, ideas for illustrations, and overall structure are original and based on the author’s own expertise and the cited medical literature. No AI tools were used to generate or influence the educational content itself.

All of the content is independent of my employer.

Use of this site implies acceptance of our Terms of Use

Contact us via E-Mail: contact@endo-cases.com