Dyslipidemias: Linking Pathogenesis to Lipid Profiles and Clinical Consequences

Definitions and Clinical Consequences

Dyslipidemia refers to an abnormal lipid profile in the circulation and is typically characterized by elevated total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and/or triglycerides (TG), reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), or a combination of these abnormalities.

LDL Cholesterol and Hypercholesterolemia

The definition of hypercholesterolemia is context-dependent and cannot be reduced to a single numerical threshold. LDL-C levels follow an approximately normal distribution in the general population. The 95th percentile corresponds to an LDL-C concentration of roughly 5.0 mmol/L (194 mg/dL). Values above this threshold raise suspicion for an underlying primary (genetic) lipid disorder and generally warrant lipid-lowering therapy irrespective of age or additional cardiovascular risk factors.

However, reliance on this percentile-based definition alone would fail to identify many individuals who derive substantial benefit from cholesterol-lowering therapy at lower LDL-C levels. This limitation reflects the fact that LDL-C is a causal and modifiable risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), as demonstrated consistently across epidemiologic studies, genetic analyses, and randomized controlled trials.

The relationship between LDL-C and ASCVD risk is continuous and log-linear: higher LDL-C levels confer progressively greater risk, and proportional reductions in LDL-C translate into proportional reductions in cardiovascular events. Meta-analyses of randomized trials indicate that each 1 mmol/L (38.7 mg/dL) reduction in LDL-C is associated with an approximate 20–25% relative reduction in major vascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, per year of treatment.

Consequently, recommendations for lipid-lowering therapy are based on both the absolute level of LDL-C and an individual’s baseline ASCVD risk. In the absence of a universally accepted definition, hypercholesterolemia may therefore be pragmatically defined as an LDL-C concentration exceeding guideline-recommended thresholds for a given ASCVD risk profile and/or an LDL-C level above the 95th percentile (>5.0 mmol/L).

Triglycerides and Hypertriglyceridemia

Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) is more readily defined from a statistical perspective due to the markedly right-skewed population distribution of triglyceride levels, with a long tail representing extreme phenotypes. The 95th percentile for TG corresponds to concentrations >3.37 mmol/L (>300 mg/dL), while the 99th percentile approaches 5.0 mmol/L (~440 mg/dL).

In clinical practice, many laboratories define the upper limit of normal for TG as >1.7 mmol/L (>150 mg/dL), which corresponds approximately to the 75th percentile. Professional societies further stratify HTG into mild, moderate, and severe categories, although definitions vary. A clinically useful distinction can be made between mild-to-moderate HTG (approximately 2–9.9 mmol/L [175–884 mg/dL]), which primarily confers excess ASCVD risk, and severe HTG (>10 mmol/L), which is associated with a markedly increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Triglyceride levels in this range occur in approximately 1 in 500 individuals and are typically associated with the presence of circulating chylomicrons.

Elevated triglyceride levels are associated with increased ASCVD risk; however, this relationship is strongly influenced by accompanying metabolic comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and diabetes. Moreover, evidence supporting pharmacologic triglyceride lowering for ASCVD risk reduction remains modest and controversial, as exemplified by divergent interpretations of outcome trials such as REDUCE-IT.

In contrast, the link between severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis is well established. Pancreatitis is thought to result from intrapancreatic lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by pancreatic lipase, generating high local concentrations of free fatty acids. These free fatty acids may induce endothelial injury, promote premature activation of trypsinogen, and trigger pancreatic autodigestion. Reduction of triglyceride levels substantially lowers pancreatitis risk. In extreme cases, lipid accumulation within the reticuloendothelial system may also lead to hepatosplenomegaly.

HDL-Cholesterol

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) has long been inversely associated with ASCVD risk in observational studies. However, a direct causal role for HDL-C in atheroprotection has not been established. Low HDL-C levels, typically defined as <0.9 mmol/L (<35 mg/dL), are considered an independent marker of increased ASCVD risk.

Importantly, Mendelian randomization studies and randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that pharmacologic interventions aimed at raising HDL-C, including niacin, fibrates, and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, do not reduce cardiovascular events when added to statin therapy. More recent evidence suggests a U-shaped relationship between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular as well as all-cause mortality, with both low and very high HDL-C concentrations associated with adverse outcomes.

Accordingly, HDL-C should be regarded as a risk marker rather than a therapeutic target. From a population perspective, HDL-C exhibits a mildly right-skewed distribution. The 2.5th percentile for HDL-C is approximately 0.7 mmol/L (27 mg/dL) in European men and 0.9 mmol/L (35 mg/dL) in European women.

Classification of Dylipidemia

Clinical and Biochemical Classification

Historically, dyslipidemias have been classified according to observable lipid phenotypes and patterns of circulating lipoproteins. The most widely known system is the Fredrickson (World Health Organization) classification, introduced in the 1960s, which categorizes dyslipidemias into five major types (I–V) based on lipoprotein fractionation, without regard to underlying etiology.

In this framework, types I and III–V are predominantly characterized by elevations in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (such as chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins), whereas type II dyslipidemia is defined by increased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), either in isolation (type IIa) or in combination with elevated VLDL (type IIb).

Although historically important, the Fredrickson classification has limited utility in contemporary clinical practice. Accurate phenotyping requires specialized techniques such as ultracentrifugation or electrophoresis, which are not routinely available in most clinical settings. Moreover, it is now recognized that most Fredrickson phenotypes are polygenic rather than monogenic, undermining the original assumption that each phenotype reflected a distinct inherited disorder. For these reasons, several experts and guideline groups (including Berberich, Amanda J, und Robert A Hegele. 2022. „A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia“. Endocrine Reviews 43 (4): 611–53. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab037.) recommend moving away from this system as a basis for diagnosis and management.

Instead, modern clinical algorithms favor a pragmatic classification based on the standard lipid panel, categorizing patients according to the dominant lipid abnormality—such as isolated hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, combined dyslipidemia, or other specific patterns—which directly informs risk assessment and treatment decisions.

Pathogenetic Classification

From a mechanistic perspective, dyslipidemias can be classified according to their underlying cause. Plasma lipid levels reflect the interaction between genetic susceptibility and secondary influences, including metabolic conditions, medications, and environmental factors.

Accordingly, dyslipidemias are broadly divided into:

Primary dyslipidemias, in which abnormal lipid levels arise predominantly from inherited genetic factors and no clear secondary cause is identified, and

Secondary dyslipidemias, where lipid abnormalities occur as a consequence of other medical conditions (such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, or nephrotic syndrome), pharmacologic therapies, or lifestyle factors.

Importantly, the majority of dyslipidemia encountered in clinical practice does not result from single-gene mutations but rather from polygenic risk operating in conjunction with dietary patterns, adiposity, insulin resistance, and other environmental exposures. Recognizing this interaction is essential for understanding disease mechanisms and tailoring effective preventive and therapeutic strategies.

The following table illustrates the most common lipid disorders with different secondary causes of dyslipidemia, adapted from Berberich, Amanda J, und Robert A Hegele. 2022. „A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia“. Endocrine Reviews 43 (4): 611–53. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab037.

From here onward, we will focus on several key genetic causes of dyslipidemia and examine how their underlying pathophysiology determines the characteristic clinical and biochemical phenotypes.

When to Suspect a Genetic Etiology

As outlined above, truly monogenic dyslipidemias account for only a small proportion of dyslipidemia cases. Nevertheless, a genetic cause should be considered when certain clinical features are present. Suspicion for a monogenic dyslipidemia is increased by:

The magnitude of lipid or lipoprotein abnormalities, with more extreme deviations suggesting a single-gene disorder

Early age at onset

The presence of characteristic physical or clinical findings (see below)

A documented family history of dyslipidemia and/or premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

The absence of identifiable secondary contributors.

Patterns of Inheritance

Many of the monogenic dyslipidemias discussed exhibit classical Mendelian inheritance, most commonly autosomal recessive. In these conditions, pathogenic variants affect both alleles of the gene (biallelic involvement), either as identical mutations (homozygosity) or as two different variants (compound heterozygosity). A hallmark of strictly recessive disorders is that individuals carrying a single pathogenic allele (obligate heterozygotes, such as parents) do not exhibit clinically or biochemically detectable abnormalities and are therefore considered asymptomatic carriers.

However, approximately one-third of monogenic dyslipidemias demonstrate a dose-dependent or additive genetic effect. In these disorders—familial hypercholesterolemia being the prototypical example—individuals with a single pathogenic allele (heterozygotes) manifest a milder phenotype compared with those carrying pathogenic variants in both alleles. This pattern has led to the use of terms such as semidominant or incompletely dominant inheritance to more accurately describe the clinical expression of these conditions.

Exercise

Let’s do a brief exercise: for each genetic disorder in the table below, predict the expected changes in the lipid profile. You can indicate the changes as + for moderate elevation or reduction, ++ for severe elevation or reduction and - if not present or normal. As a hint, refer to the lipid metabolism illustration highlighting the relevant mutations. The answers will be provided at the end of this clinical pearl.

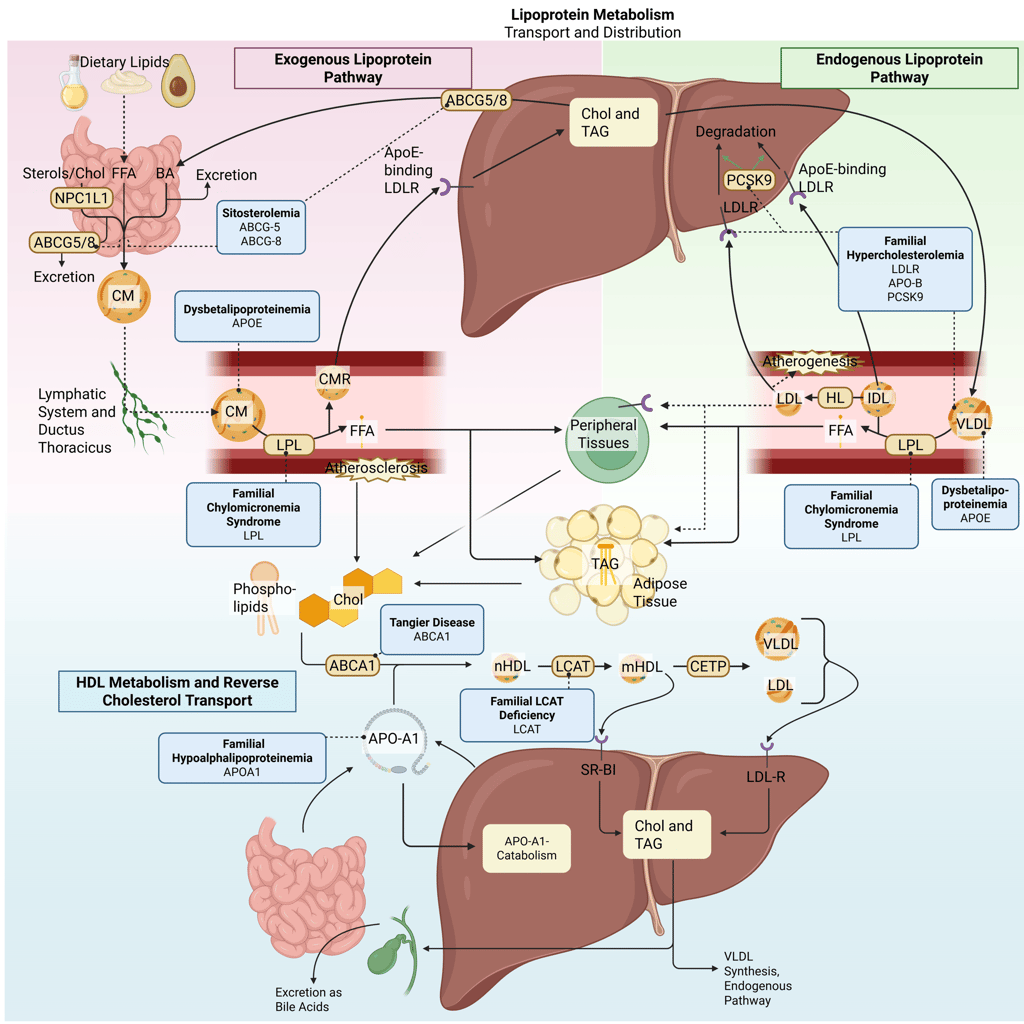

Detailed Illustration of the lipoprotein metabolism in the human body. Blue boxes: genetic dyslipidemias in bold, Gene mutations in regular. Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, CMR: Chylomicron Remnants, TAG: Triacylglycerol, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, HDL: High Density lipoprotein, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, VLDL: Very Low Density Lipoprotein, LPL: Lipoprotein Lipase, HL: Hepatic Lipase, LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, CETP: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, LDLR: LDL-Receptor, ABCG5: ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 5, ABCG8: ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 8; ABCA1: ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A1

Genetic Dyslipidemias with severely elevated LDL-C: Monogenic Hypercholesterinemia

Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH)

Causative Genes

LDLR (most common; >90% of genetically confirmed cases)

APOB (≈5–10%)

PCSK9 (gain-of-function variants; <1%)

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal semidominant (incompletely dominant)

Heterozygous individuals exhibit a milder phenotype

Biallelic involvement results in a markedly more severe clinical and biochemical presentation

Prevalence

Heterozygous FH (HeFH): approximately 1 in 300 individuals in the general population, with higher prevalence reported in certain geographic regions

Homozygous FH (HoFH): rare, occurring in approximately 1 in 160,000 to 1 in 450,000 individuals

Pathogenetic Mechanisms

FH is characterized by impaired hepatic clearance of circulating low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles due to defects in LDL receptor–mediated uptake:

LDLR loss-of-function mutations reduce the number or function of LDL receptors on hepatocytes, leading to diminished LDL-C uptake by the liver and accumulation of LDL particles in the circulation.

APOB mutations affect apolipoprotein B-100, the principal ligand required for LDL binding to the LDL receptor. Structural alterations in the LDLR-binding domain reduce receptor affinity and impair LDL particle internalization.

PCSK9 gain-of-function mutations increase lysosomal degradation of LDL receptors, reducing receptor availability on the hepatocyte surface and further limiting LDL clearance.

Biochemical Features

Heterozygous FH (HeFH):

LDL-C typically 2–3 times above normal

Untreated LDL-C commonly ranges from 5–10 mmol/L (190–400 mg/dL)

Significant interindividual variability depending on genotype and modifying factors

Homozygous FH (HoFH):

Markedly elevated LDL-C levels

Untreated LDL-C typically >13 mmol/L (>500 mg/dL) and often 13–20 mmol/L (500–800 mg/dL) or higher, particularly in LDLR-null variants

Additional lipid abnormalities:

HDL-C may be reduced

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is frequently markedly elevated

Clinical Manifestations

Premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)

Early-onset coronary artery disease, often in childhood or young adulthood in HoFH

Tendon xanthomas (e.g., Achilles, extensor tendons of the hands)

Xanthelasma and corneal arcus, particularly at a young age

Aortic valve disease, especially supravalvular aortic stenosis in HoFH

Sitosterolemia

Causative Genes

ABCG5

ABCG8

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal recessive

Pathogenetic Mechanism an Biochemical Pattern

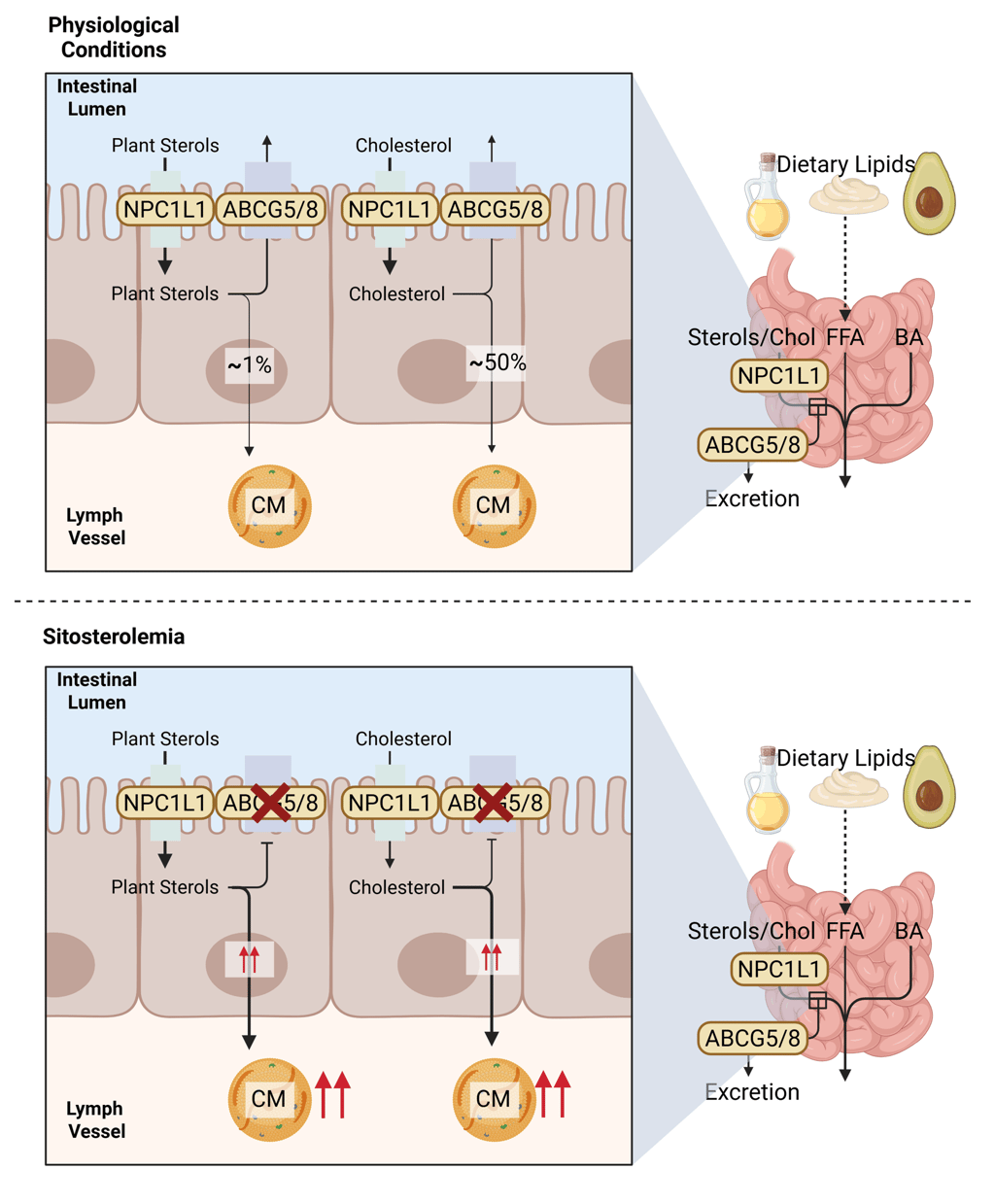

Sitosterolemia results from biallelic loss-of-function mutations in ABCG5 or ABCG8, which encode sterol efflux transporters expressed in enterocytes and hepatocytes. Under physiological conditions, these transporters limit intestinal absorption of sterols and facilitate biliary excretion of both dietary cholesterol and noncholesterol plant sterols.

Loss of transporter function leads to excessive intestinal absorption and impaired biliary elimination of sterols, resulting in accumulation of cholesterol and plant-derived sterols in plasma and tissues. Consequently, patients exhibit elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), which can phenotypically resemble familial hypercholesterolemia.

A distinguishing biochemical feature is markedly increased plasma levels of plant sterols, particularly:

β-sitosterol

Campesterol

Stigmasterol

Measurement of plasma plant sterols is diagnostic.

Illustration of the physiological function of NPC1L1, ABCG5 and 8 in intestinal Cholesterol and Plant Sterol uptake and secretion (above) and pathogenesis of Sitosterolemia (below). Chol: Cholesterol, CM: Chylomicrons, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, ABCG5: ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 5, ABCG8: ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 8

Clinical Manifestations

Xanthomas: tendinous, tuberous, and cutaneous

Splenomegaly

Premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, claudication, arterial bruits

Hematologic abnormalities: hemolysis and hemolytic anemia

Platelet dysfunction: impaired aggregation leading to easy bruising or bleeding

Genetic Dyslipidemias with severely depressed HDL-C: Monogenic Hypoalphalipoproteinemia

Familial Hypoalphalipoproteinemia

Causative Gene

APOA1

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal semidominant

Phenotypic severity depends on monoallelic versus biallelic involvement

Pathogenetic Mechanism

Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) is the principal structural and functional protein of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles and is essential for HDL biogenesis, maturation, and stability. ApoA-I serves as the initial acceptor of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids from peripheral tissues via the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1), enabling the formation of nascent HDL particles.

Loss-of-function mutations in APOA1 impair apoA-I synthesis or function, severely limiting cholesterol efflux from peripheral cells and disrupting HDL particle formation. This results in defective reverse cholesterol transport and promotes cholesterol accumulation within tissue macrophages, contributing to xanthoma formation and accelerated atherosclerosis.

Biochemical Features

Biallelic variants:

Near-absent or undetectable HDL-C

Absent or markedly reduced plasma apoA-I

Monoallelic variants:

Moderately reduced HDL-C

Reduced apoA-I levels

Clinical Manifestations

Xanthomatosis, including cutaneous lesions and involvement of interdigital web spaces

Increased risk of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)

Tangier Disease

Causative Gene

ABCA1

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal semidominant

Biallelic mutations produce the classic severe phenotype

Monoallelic carriers exhibit moderate HDL reduction with minimal clinical manifestations

Pathogenetic Mechanism

ABCA1 is a critical membrane transporter that mediates the efflux of cholesterol and phospholipids from peripheral cells to apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), initiating the formation of nascent HDL particles. Loss-of-function mutations in ABCA1 disrupt this process, leading to severely reduced HDL-C and impaired reverse cholesterol transport. As a result, cholesterol accumulates in various tissues, contributing to characteristic clinical features.

Biochemical features

Biallelic variants: absent HDL-C and apoA-I; may show stomatocytes on peripheral blood smear

Monoallelic variants: moderately reduced HDL-C; typically asymptomatic

Clinical Manifestations

Hepatosplenomegaly

Corneal opacities

Enlarged orange tonsils

Deposition of cholesterol esters in lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, spleen, and tonsils

Dermatologic features: dry, brittle skin, hair, and nails

Neurologic involvement: demyelinating sensory, autonomic, and motor neuropathies

Cardiovascular manifestations: premature coronary artery disease, angina, carotid bruits, and intermittent claudication

Familial LCAT Deficiency

Causative Gene

LCAT

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal recessive

Pathogenetic Mechanism

LCAT (lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase) is crucial for the esterification of free cholesterol on nascent HDL particles, a key step in HDL maturation. Loss-of-function mutations in LCAT prevent the conversion of free cholesterol into cholesteryl esters, resulting in impaired formation of mature, spherical HDL particles and defective reverse cholesterol transport.

Biochemical features

Low circulating HDL-C

Reduced plasma esterified cholesterol

Low apoA-I and apoA-II

Elevated plasma free cholesterol and triglycerides

Clinical Manifestations

Ocular: corneal lipid deposits and opacities (severe forms referred to as “Fish Eye Disease”)

Hematologic: anemia

Renal: proteinuria, renal failure, foam cells in bone marrow and glomeruli

Other: impaired cholesterol transport leading to increased atherosclerotic risk

Genetic Dyslipidemias with elevated Triglycerides: Monogenic Hypertriglyceridemia

Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS)

Causative Genes

LPL (most common; >80% of cases)

Other rare genes affecting LPL function or cofactors

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal recessive

Pathogenetic Mechanism

FCS arises from biallelic loss-of-function mutations in LPL or related genes required for lipoprotein lipase activity. LPL is essential for hydrolyzing triglycerides in chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) into free fatty acids, enabling their uptake by peripheral tissues. Loss of LPL function results in impaired clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, causing severe hypertriglyceridemia.

Biochemical features

Extremely elevated plasma triglycerides (often >2000 mg/dL / >22.6 mmol/L)

Lipemic plasma

Biallelic individuals typically present in childhood

Monoallelic relatives show highly variable triglyceride levels, ranging from normal to severely elevated

Clinical Manifestations

Gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, failure to thrive

Pancreatic: high risk of acute pancreatitis

Other findings: lipemic plasma, eruptive xanthomas, lipemia retinalis, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice

Dysbetalipoproteinemia

Causative Gene

APOE (most commonly APOE2 homozygosity)

Inheritance Pattern

Autosomal recessive

Pathogenetic Mechanism

Dysbetalipoproteinemia arises from defective binding of apoE2 to hepatic lipoprotein receptors (primarely the LDL-Receptor and LDL receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1)). This impairs clearance of chylomicron and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) remnants, causing accumulation of triglyceride- and cholesterol-rich remnant lipoproteins.

Biochemical features

Moderate elevations of both triglycerides and total cholesterol

Predominantly remnant lipoproteins present

Clinical Manifestations

Xanthomas: tuberoeruptive lesions, palmar crease xanthomas

Cardiovascular risk: premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Pancreatitis: uncommon, unlike in familial chylomicronemia syndrome

Genetic Diseases with Secondary Dyslipidemia

Genetic Lipodystrophies

Causative Genes

Partial lipodystrophies:

LMNA (autosomal dominant)

PPARG (autosomal dominant)

Others

Generalized lipodystrophies: multiple genes depending on subtype

Inheritance Pattern

Partial lipodystrophies: autosomal dominant

Generalized lipodystrophies: variable, often autosomal recessive

Pathogenetic Mechanism

Lipodystrophies arise from genetic defects that result in loss or absence of functional adipose tissue. Impaired triglyceride storage leads to:

Increased circulating triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs)

Enhanced hepatic triglyceride synthesis

Ectopic lipid deposition in liver, muscle, and other non-adipose tissues

Insulin resistance and secondary dysregulation of lipid metabolism

Biochemical features

Partial lipodystrophies: elevated triglycerides (can be severe in 10–20% of cases)

Generalized lipodystrophies: elevated triglycerides, frequently severe; elevated liver enzymes

Clinical Manifestations

Partial lipodystrophies:

Distinctive regional lipoatrophy with compensatory lipohypertrophy in unaffected areas

Insulin resistance

Recurrent pancreatitis

Generalized lipodystrophies:

Near-total absence of subcutaneous fat

Insulin resistance and diabete

Recurrent pancreatitis

Hepatosplenomegaly

Key Takeaways and Exercise Review

The definition of dyslipidemia—and particularly hypercholesterolemia—is inherently context dependent and cannot be reduced to a single numerical cutoff. Lipid levels must be interpreted in relation to population distributions, absolute concentrations, and, most importantly, an individual’s baseline risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. This concept underpins the shift in clinical practice away from rigid, phenotype-based classifications toward more pragmatic approaches that integrate routine lipid profiles with clinical risk assessment and underlying pathophysiology.

Most dyslipidemias encountered in clinical practice arise from a polygenic genetic background interacting with secondary factors such as diet, obesity, insulin resistance, medications, or systemic disease. In contrast, true monogenic dyslipidemias are rare, but they are characterized by extreme lipid abnormalities, earlier onset, and often distinctive clinical features that warrant focused diagnostic evaluation. Importantly, the biochemical lipid profile observed in any given patient directly reflects the site of disruption within lipid metabolism: defects in LDL clearance predominantly elevate LDL-C, impaired HDL formation or maturation results in low HDL-C, and disturbances in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein processing lead to hypertriglyceridemia.

A clear understanding of lipid physiology and pathophysiology therefore provides the framework for interpreting lipid profiles, recognizing when a genetic disorder should be suspected, and selecting rational, mechanism-based therapeutic strategies.

The following table summarizes the key changes in the lipid profile according to the genetic cause of dyslipidemia.

References

All graphical Illustrations were created in https://BioRender.com

Bays, Harold E., Peter H. Jones, W. Virgil Brown, und Terry A. Jacobson. 2014. „National Lipid Association Annual Summary of Clinical Lipidology 2015“. Journal of Clinical Lipidology 8 (6, Supplement): S1–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2014.10.002.

Beheshti, Sabina O., Christian M. Madsen, Anette Varbo, und Børge G. Nordestgaard. 2020. „Worldwide Prevalence of Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Meta-Analyses of 11 Million Subjects“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 75 (20): 2553–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.057.

Berberich, Amanda J, und Robert A Hegele. 2022. „A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia“. Endocrine Reviews 43 (4): 611–53. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab037.

Bosner, M. S., L. G. Lange, W. F. Stenson, und R. E. Ostlund. 1999. „Percent Cholesterol Absorption in Normal Women and Men Quantified with Dual Stable Isotopic Tracers and Negative Ion Mass Spectrometry“. Journal of Lipid Research 40 (2): 302–8.

Bydlowski, Sergio Paulo, und Debora Levy. 2024. „Association of ABCG5 and ABCG8 Transporters with Sitosterolemia“. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1440: 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43883-7_2.

Collins, Rory, Christina Reith, Jonathan Emberson, u. a. 2016. „Interpretation of the Evidence for the Efficacy and Safety of Statin Therapy“. Lancet (London, England) 388 (10059): 2532–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5.

D’Erasmo, Laura, Alessia Di Costanzo, Francesca Cassandra, u. a. 2019. „Spectrum of Mutations and Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in Genetic Chylomicronemia Syndromes“. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 39 (12): 2531–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313401.

Eckardstein, Arnold von, Børge G. Nordestgaard, Alan T. Remaley, und Alberico L. Catapano. 2023. „High-Density Lipoprotein Revisited: Biological Functions and Clinical Relevance“. European Heart Journal 44 (16): 1394–407. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac605.

Fernández-Higuero, J. A., A. Etxebarria, A. Benito-Vicente, u. a. 2015. „Structural Analysis of APOB Variants, p.(Arg3527Gln), p.(Arg1164Thr) and p.(Gln4494del), Causing Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Provides Novel Insights into Variant Pathogenicity“. Scientific Reports 5 (Dezember): 18184. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18184.

Hachem, Sahar B., und Arshag D. Mooradian. 2006. „Familial Dyslipidaemias“. Drugs 66 (15): 1949–69. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200666150-00005.

Hadjiphilippou, Savvas, und Kausik K. Ray. 2019. „Cholesterol-Lowering Agents“. Circulation Research 124 (3): 354–63. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313245.

Hegele, Robert A, Jan Borén, Henry N Ginsberg, u. a. 2020. „Rare dyslipidaemias, from phenotype to genotype to management: a European Atherosclerosis Society task force consensus statement“. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 8 (1): 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30264-5.

Jellinger, Paul S., Yehuda Handelsman, Paul D. Rosenblit, u. a. 2017. „American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Guidelines for Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease“. Endocrine Practice 23 (April): 1–87. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP171764.APPGL.

Khalil, Yara Abou, Jean-Pierre Rabès, Catherine Boileau, und Mathilde Varret. 2021. „APOE Gene Variants in Primary Dyslipidemia“. Atherosclerosis 328 (Juli): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.05.007.

Knebel, Birgit, Dirk Müller-Wieland, und Jorg Kotzka. 2020. „Lipodystrophies-Disorders of the Fatty Tissue“. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21 (22): 8778. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21228778.

Nordestgaard, Børge G. 2016. „Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: New Insights From Epidemiology, Genetics, and Biology“. Circulation Research 118 (4): 547–63. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306249.

„Olezarsen, Acute Pancreatitis, and Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome | New England Journal of Medicine“. o. J. Zugegriffen 29. Dezember 2025. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2400201?utm_source=openevidence.

Ostlund, Richard E. 2002. „Phytosterols in Human Nutrition“. Annual Review of Nutrition 22: 533–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.020702.075220.

Ramasamy, I. 2016. „Update on the molecular biology of dyslipidemias“. Clinica Chimica Acta 454 (Februar): 143–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2015.10.033.

Razavi, Alexander C., Vardhmaan Jain, Gowtham R. Grandhi, u. a. 2024. „Does Elevated High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Protect Against Cardiovascular Disease?“ The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 109 (2): 321–32. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgad406.

Reijman, M. Doortje, D. Meeike Kusters, und Albert Wiegman. 2021. „Advances in Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in Children“. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health 5 (9): 652–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00095-X.

Saadatagah, Seyedmohammad, Merin Jose, Ozan Dikilitas, u. a. 2021. „Genetic Basis of Hypercholesterolemia in Adults“. NPJ Genomic Medicine 6 (1): 28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-021-00190-z.

Santos, Raul D., Samuel S. Gidding, Mafalda Bourbon, u. a. 2025. „Recent Advances in Research and Care of Familial Hypercholesterolaemia“. The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology 13 (12): 1054–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(25)00286-4.

Silverman, Michael G., Brian A. Ference, Kyungah Im, u. a. 2016. „Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis“. JAMA 316 (12): 1289–97. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.13985.

Simha, Vinaya, und Abhimanyu Garg. 2009. „Inherited Lipodystrophies and Hypertriglyceridemia“. Current Opinion in Lipidology 20 (4): 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0b013e32832d4a33.

Sturm, Amy C., Joshua W. Knowles, Samuel S. Gidding, u. a. 2018. „Clinical Genetic Testing for Familial Hypercholesterolemia: JACC Scientific Expert Panel“. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 72 (6): 662–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.044.

Tada, Hayato, Akihiro Nomura, Masatsune Ogura, u. a. 2021. „Diagnosis and Management of Sitosterolemia 2021“. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 28 (8): 791–801. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.RV17052.

„Triglycerides and Cardiovascular Disease | Circulation“. o. J. Zugegriffen 29. Dezember 2025. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed.

Witztum, Joseph L., Daniel Gaudet, Steven D. Freedman, u. a. 2019. „Volanesorsen and Triglyceride Levels in Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome“. New England Journal of Medicine 381 (6): 531–42. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1715944.

© 2025 EndoCases. All rights reserved.

This platform is intended for medical professionals, particularly endocrinology residents, and is provided for educational purposes only. It supports learning and clinical reasoning but is not a substitute for professional medical advice or patient care. The information is general in nature and should be applied with appropriate clinical judgment and in accordance with local guidelines.

Portions of the text on this website were edited with the assistance of Artificial Intelligence to improve grammar and phrasing, as English is not my first language. All medical content, ideas for illustrations, and overall structure are original and based on the author’s own expertise and the cited medical literature. No AI tools were used to generate or influence the educational content itself.

All of the content is independent of my employer.

Use of this site implies acceptance of our Terms of Use

Contact us via E-Mail: contact@endo-cases.com